After more than a year of crushing inside-ness, of isolation and lives chiseled down to the four walls of our homes, an escape hatch into the past — or even simply into different scenery — is an alluring thought. The large format landscape photographs in Jellel Gasteli’s show, En Tunisie, on view at Semla Feriani gallery in Sidi Bou Said, Tunisia form such a portal into a world unfurling in layers of familiarity, mystery and time.

When Gasteli was in his early twenties, he set out on a two-week journey through Tunisia, the country where he was born and raised but about which he knew very little. It was the late 1970s and a family friend, also curious about the places and people in the less-developed regions of the country’s interior, gave him a camera and two rolls of film, and asked him to bring back photos of the trip.

The young Gasteli had never operated a camera before and was unsure if he could manage. Undeterred, his friend adjusted the settings and told him: “Just push the button.”

A fortnight later, after a transformative journey that wound him through farmlands and salt flats, past ancient ruins and obscure outposts, and into the homes and lives of people wildly different than himself, Gasteli returned to the capital and dropped his film at a lab, anxious to see what he had captured. But two days later, the lab technician handed him back an envelope filled with two blank rolls of film: the camera’s settings had been jostled, and not a single frame was exposed correctly.

This early failure both crushed and motivated Gasteli, who went on to pursue a degree at the National Institute of Photography in Arles, France. For years, his photographic work focused on other countries on the Mediterranean — Morocco, France — but never his homeland.

Nearly 20 years after Gasteli’s first journey through Tunisia, an Italian collector named Marco Rivetti approached him with an ambitious proposition: to create a body of work that captured the essence of Tunisia, it’s land, history and people, for a photobook.

The artist set out to recreate his previous voyage, and to “get back all the emotions and impressions I had at the time”, he says.

The resulting body of work, taken over the course of several years and in every corner of Tunisia, is a grand meditation on the past – both of a country and of the id of a young artist. Compiled into a book, also titled En Tunisie, it was published in 1997.

Now, for the first time, nearly two dozen of those images are on display as rich, large-format prints that engulf and transport the viewer into landscapes that are at once emotional and reassuring in their subjects’ persistence across time.

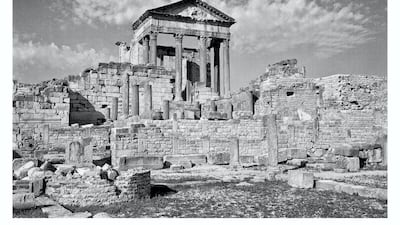

That persistence is most legible in a series of images of ancient Roman ruins photographed in the high relief of late afternoon Mediterranean light. That the relics have remained largely empty of tourists over the years is a boon for Gasteli; pieces like Mahdia 15 or Dougga 2 could have come from the lens of the early photographer Girault de Prangey, who captured Greek and Roman temples in the eastern Mediterranean in the 1840s. (Though the most striking comparison between the two is not the ancient Capitols, but twin images of lone palm trees that are at once painterly and lovely and extraordinarily sad.)

Gasteli also drew great inspiration from the Sahara, and many of the most seductive images in the show draw on the curves and lines of the dunes found throughout the south of Tunisia. The sand gathers light the way flesh would, and there are hits of sensuality in images like Remel El Abiod No. 01 and Remel El Abiod No. 02, the latter of which almost conjures the image of a woman's exposed navel.

But some of the most intriguing and arresting images in the show are not from the unrelenting expanse of the desert or the forums of history, but from the private garden of Leila Menchari, the former artistic director of Hermes. Gasteli stumbled into her garden through a back gate while exploring the resort town of Hammamet in the mid 1990s, and found it so inspiring, along with its owner, that he returned often in the following years to take pictures there.

Indeed the show's greatest triumph is Hammamet, a mysterious image of a lily in a beam of early spring light seen from a distance through layers of foliage. The tones of the print are so fine, the grain so elegantly pronounced, that the image appears almost as a charcoal drawing.

Although the first edition of En Tunisie (the streamlined second edition of which is being published in tandem with the exhibition) comprised nearly an equal number of landscapes and ethnographic images of the inhabitants of Tunisia, only four of the exhibition's photographs include people. Perhaps it is because, unlike the desert or the coastline, people do not stand the test of time. Their presence can instantly date an image, marring the illusion of timelessness.

Gasteli’s compositions are not complicated or demanding. They are, simply, relieving. The show itself was conceived as a gift to the viewer.

“With all the depression around Covid, the mutation of our landscapes and cities,” he said in an interview, “it felt like the right moment to offer some – excuse me for the word – just some beauty.”