When you cast your eye over the images Stuart Humphryes posts on social media, you'd think they were modern-day fashion shoots for a magazine. But they're not. In reality, many of them were taken more than a century ago, yet they're sharp, beautiful and full of colour.

Humphryes, 50, who's known as BabelColour on social media, transforms archival snaps into what you'd assume are images taken on a mobile phone or a digital camera.

"I don't actually colourise because I work with early colour photographs that were taken in colour. I enhance what is already there," he tells The National.

Every day, after finishing his 9 to 5 job in London, Humphryes dedicates his evenings to this creative pursuit. The local government worker, who has a background as a colouriser, spends hours editing images and videos in his spare time.

Click through the gallery below to discover five exclusive photographs by BabelColour shared with 'The National':

It was in June this year that Humphryes changed his Twitter account to BabelColour and started sharing these images online for the first time. Since then, the response has been overwhelming. In less than three months, he has gained more than 100,000 new followers, receiving messages from people around the world (sometimes in so many different languages he had to use Google Translate) praising his work.

"The more people joined me, the more varied my photographs became. So I started repairing and enhancing photographs from across the world, from the Middle East and Africa to India."

This led to him starting an Instagram account a few weeks ago, something he never imagined he'd do considering he doesn't even own a mobile phone or a tablet. His account already has more than 10,000 followers.

"With these photographs, I'm not trying to make them look like they were taken in 1918," he says. "I'm trying to make them look contemporary; I'm trying to make them look like they were taken on an iPhone today rather than 100 years ago."

What Humphryes does goes beyond image editing and Photoshop. Instead he is tricking people into seeing the works in a completely new way.

"It's not really a case of restoration. It's a case of changing them so that people's perception of them changes – by making them more contemporary and modern, it breaks down the barriers of time. So people look at the photographs and can relate to them as if they are real people they could meet today, rather than ghosts from another period," he says.

The very first colour photographs were taken at the start of the 20th century using autochrome plates that captured colour. While the process was considered to be a successful first attempt at moving away from black-and-white photography, the autochromes were fragile and colours didn't age well. Humphryes, however, works with a digital version of the autochrome to boost the colours that have faded within it.

"Imagine there's a piece of music playing and it's quiet, you can barely hear it. Well, if you turn the volume up, you are increasing the level of the sound, but you are not adding any new music," he explains. "What I'm doing with colour is I'm boosting it so it becomes clearer to see with the naked eye. I'm not adding any of my own."

Most of Humphryes's work is done using software widely available on the market today, such as Adobe, which he uses to remove grain and dirt from an image, repair any damage, balance the light and boost the colour. He then uses AI technology to make the photo look like it was taken on a modern camera.

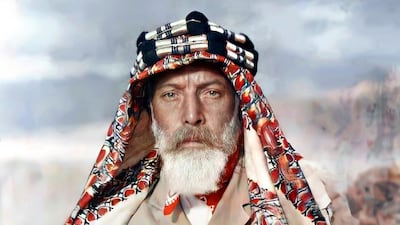

For example, this 102-year-old portrait of Fayz Bey el Azm (companion of Prince Faisal, who led the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War), taken by French photographer Paul Castelnau in Jordan, looks barely a decade old.

Today, Humphryes receives messages from teachers asking for permission to use photographs he's enhanced in their classes, something that brings him much joy.

"People seem to see the First World War very much as a black and white war. Seeing images of the soldiers in colour is a completely different experience, so I'm very happy for teachers and children to engage in history in a new way, because they do see differently in colour."

He has also received many requests to edit personal photos, which he has had to politely decline.

"People ask me every day, but I explain to them that if I do it for them, I have to do it for other people," he says. "At the moment, I don't have that capacity."

However, he is thinking about what the future of this project could hold.

"Everybody seems to be clamouring for a book," he says. "I would love to do a book or just something so that it's in a physical medium that people can purchase and own."

While the prospect of a book intrigues him, it's the technology at our fingertips that he describes as "exciting".

"It makes you wonder where we're going to be in five years' time and 10 years' time."