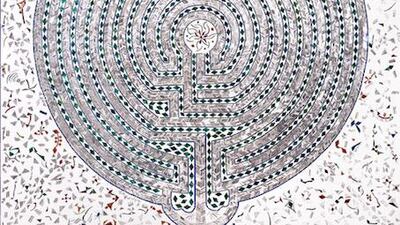

In the sixteenth century, so the story goes, Iran imported glass from Europe, but it would arrive fractured and broken after its long journey. Artisans began using the shards to decorate mosques, creating the intricate mosaics known as aineh-kari, in which mosques' domed ceilings and fretted walls are transformed into sparkling arrays.

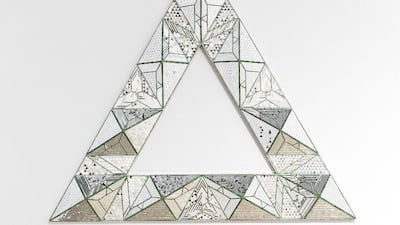

Years later, the Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who died on Saturday in Tehran, used this technique as the inspiration for her distinctive sculptures and wall-hung works. In her hands traditional Islamic geometry was rendered into an active, almost destabilising interplay of light and reflection.

Click though to see a gallery of some of Farmanfarmaian's work:

Farmanfarmaian was born in Qazvin, Iran in 1924 to a prominent Ottoman Empire family. She was rare among artists of her generation to travel abroad; after attending the Fine Arts College of Tehran, she moved to New York, where she mixed with many of the leading artists of the time, such as Jackson Pollock, Frank Stella, and Louise Nevelson, and, later, Andy Warhol. Reportedly, she gave him one of her mirrored disco-like balls, and he kept it in pride of place on his desk. She studied at the Parsons School of Design, graduating in 1949, and was a member of the prestigious New York Art Students' League.

She returned to Iran after 12 years, and her work really took off after a 1975 visit to the Shah Cheraq shrine in Shiraz. It was there, in a road to Damascus moment, that she was struck with the idea for mirrored geometries. In her 2013 memoir, she recalled the shrine as “architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance in space, in prayer,” and sought to bring its effects into contemporary art.

The solid forms of the spheres, helices and polyhedrons she made become fonts of light in themselves: not solid but made of pure appearance, shifting as the viewer moved around them. In other altar-piece-like works she uses the folding doors and floral motifs reminiscent of mosques, updated for a contemporary language.

She and her second husband Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian were exiled in New York during the Iranian Revolution, and much of the work that she had made in Iran in the previous years was entirely lost. She returned again to Iran in the early 1990s, installing herself back in Tehran. There she resumed her practice of making mosaics, which she was able to make again in earnest with the help of trained artisans.

Her work was given renewed attention later in her life. She was one of the first artists signed to the Third Line when it opened in Dubai in 2005, and her work also became known in the UAE through research conducted by Negar Azimi of Bidoun magazine. A museum devoted to her works, called the Monir Museum, opened in 2017 in Tehran: the first museum in Iran dedicated solely to a female artist. And a major solo show, "Infinite Possibilities," introduced her practice to audiences in Portugal and New York, where it was held at the Guggenheim in 2015.

Tributes to her work in the UAE flooded social media on Sunday, the day after her death. Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi shared a picture of the two, hand in hand, looking at some of her floral and mirrored mosaics. Her solo exhibition, Sunset, Sunrise, held at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin last year, is slated to come to the Sharjah Art Foundation later this year.