Spanning the roadsides and adhering to the walls of cities across Lebanon, Iraq and Palestine are posters bearing the faces of martyrs, the dead and missing victims of conflicts old and new. For years, Taysir Batniji has been fascinated by these posters – not because of the people they commemorate, but because of the way they gradually dissolve, disintegrate and disappear.

“What interested me about these posters or portraits was the decomposition of the photo as a representation of the dead. For me, it was a kind of parallel of the disappearance of the person, through the disappearance of the representation,” says the Palestinian artist, who took a series of photographs of these posters in Gaza in 2001.

Eighteen years later, Sand Comes Through the Window, Batniji's solo show at Mina Image Centre in Beirut, reveals his ongoing interest in representation, memory and imagery. Traces, a series dating from 2016, greets visitors to the exhibition. From a distance, the 10 framed works look like photographs showing fragments of packing tape or the residue of glue left after a poster is removed. In fact, they are deceptively delicate watercolour paintings that depict the stains left behind when a poster has finally disappeared. For the artist, these forms were an indication of "absence and presence at the same time".

"The death of my brother in 1987 was the inspiration for these works, and for the focus in my work on presence and absence. It started in 1997 when I was a student, but it took me time to realise that this was the motivation to continue with this concept, which I've tried to deal with through different media, like drawing, installations, site-specific works."

Batniji was born and raised in Gaza before leaving in 1993 to study art in Europe. A Paris resident since 1996, he has spent more than two decades creating work about Gaza and his relationship with his homeland, despite facing increasing difficulty in travelling home after 2006, when clashes with Israel intensified. Although he has not been to Gaza since 2012, he has continued to find ways to create works on Palestine.

Sand Comes Through the Window brings together five series of works dating from 2006 to 2017. Thematically and materially diverse, they exemplify both Batniji’s imaginative use of media and his obsession with image-making, often using existing photographs as a starting point.

To My Brother (2012) foretells the experimental quality of Traces, in which watercolour mimics photography, as well as its thematic exploration of absence and presence. Batniji created a series of images delicately carved by hand into the surface of white sheets of paper, all inspired by photographs taken at his brother's wedding in 1985. These photographs are bittersweet for the artist. Two years after the marriage, the First Intifada began. The groom was killed by an Israeli sniper nine days in.

Batniji's etchings enforce a level of intimacy. From a distance, they resemble blank sheets of paper, but on close inspection, the viewer can see the details. The painstaking carvings evoke the emotional power of memory and the pain of absence, creating phantom echoes of an occasion and a person both lost to time.

“I’ve always wanted to avoid political discourse and the stereotyped photos and images of Palestine that people have through reportage about the reality of the Palestinian conflict,” Batniji explains. “As an artist, I always want to place my work in a more universal space … In most of my work, the point of departure is my personal experience and my personal life. As a Palestinian, of course, my personal experience reflects the collective experience, in one way or another.”

Disruptions (2017), the newest body of work, also explores the artist's relationship with his family, conveying the emotional toll of life in exile. A series of screenshots taken during WhatsApp video calls to Gaza document the pixelation and distortions caused by the internet, which is often disrupted by incidences of conflict. Batniji took the screenshots over two years during family conversations, continuing until his mother died at the end of 2017.

"It's a way of reflecting the distance, the impossibility of going back home and the difficulty keeping in contact with the country, taken from my personal experience," he says. "That way, you don't need to make a discourse about exile, about the possibility of being home … My work is trying to deal with difficulties in a way that you are not just affected by things, you are trying to be active. You're not just suffering what is happening, but using it as material for your art."

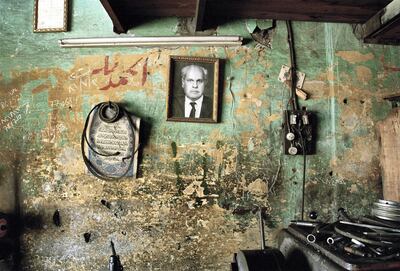

The two oldest series of works on show, Fathers (2006) and Watchtowers (2008), are more traditional photo series documenting the realities of life in Palestine. The former are colourful photographs taken in shops, cafes and workplaces in Gaza where portraits of the companies' founders hang on the walls, a common practice that establishes a link between past and present while blurring the lines between the private and public spheres.

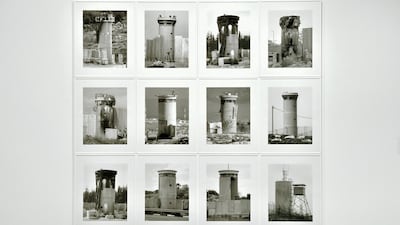

Watchtowers, too, has its roots in existing photographs. The black-and-white series was inspired by Bernd and Hilla Becher's photographs of water towers in Europe. Struck by their similarities to Israeli military watchtowers in the West Bank, Batniji created his series as a dark mirror. Unable to visit the West Bank himself, he employed a young Palestinian photographer as his proxy.

From a distance the photographs appear uniform, but closer inspection reveals inconsistencies borne of the difficulties and dangers of photographing military sites. Some of the images are blurred, taken while on the move or from a great distance, while others are slightly off-kilter or off-centre, contrasting with the studied perfection of the original series. These inconsistencies only emphasise the true function of these watchtowers "as places for surveillance, for observation, for oppression and for military presence – and the impossibility of movement for Palestinians from one place to another," Batniji says.

Watchtowers is the most overly political work in the exhibition and exemplifies the difficulties of working as an artist in exile. But despite the drawbacks, Batniji credits his long years living outside his homeland with his ability to achieve a sense of emotional distance in his work while continuing to tell human stories. "When you are inside, you don't have the same [ability] to look at and to interpret events," he explains. "Maybe the distance allows me to look at things in a deeper way."

Sand Comes Through the Window is at Mina Image Centre in Beirut until August 11