The new Mosul Heritage Museum in Iraq is inviting people to experience its greatest historical sites — in virtual reality.

Having opened earlier this year as a permanent exhibition, the immersive show gives Iraqis a new way to explore their most cherished monuments that have been destroyed.

Through painstaking documentation, computer technology and virtual-reality artistry, Qaf Lab, an innovation hub in Mosul that supports Iraqi entrepreneurs, has reconstructed five heritage sites destroyed or damaged by ISIS during their three-year occupation of Mosul from 2014.

Abdullah Bashar was 16 at the time and saw first-hand the devastation the group caused. Five years later, while studying architecture at the University of Mosul, he was struck with an idea.

“We were studying the heritage of our city and how it used to be,” he tells The National. “I thought then about virtual reality and what a creative way it could be to show these destroyed sites and our heritage to the people.”

Bashar and two of his university peers started virtually reconstructing the great Al Nuri mosque, famous for its leaning minaret known as Al Hadba or "the hunchback".

Built in the late 12th century, Al Nuri mosque was a prominent landmark and part of Mosul’s visual identity until it was destroyed, along with its minaret, by ISIS during the Battle of Mosul in 2017.

Although Unesco, in partnership with the UAE and the government of Iraq, began efforts to reconstruct the building last year, in 2019, Bashar started recreating the mosque in virutual reality.

When he presented his work to Qaf Lab, the company was so impressed it hired Bashar and his team to continue with their project full time.

Two years later, after the addition of four more heritage sites and after posting their work online, Bashar was invited to create the exhibition now on view at the Mosul Heritage Museum.

Ayoub Younes, founder of the museum, saw the project as an opportunity to connect with young people in Mosul. "This exhibition is aligned with the three goals of the museum,” he says.

“The first, to bring to life the intellectual legacy of this city. The second, to revitalise the tourism industry. And third, to work on initiatives we hope will preserve the legacy of this civilisation.”

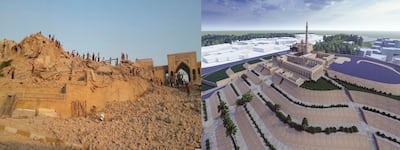

The heritage sites that have been virtually reconstructed depict and document their current state, alongside digital restorations of what they looked like before their destruction by ISIS.

The Umayyad Mosque — the first built in Mosul and fifth in the Islamic world, constructed in the year 642 — is also featured in the exhibition, alongside the Syriac Catholic Al Tahera Church, built between 1859 and 1862, Al Nabi Yunus Mosque, home to a tomb believed to be that of the prophet Jonah, and the great temple of Hatra, a Unesco World Heritage Site that features an enormous structure made of columns and smaller temples.

Younes says that while visitors, mostly residents of Mosul, have connected emotionally to the exhibition, modern technology is also a vital tool to educate and create awareness of the city’s heritage.

“The reactions from many visitors have been positive,” Younes says. “Not only because this is something new but also because visitors can also experience entering ancient heritage sites that have since been destroyed.”

After seeing the renderings of Mosul's reconstructed heritage sites, architect Raffaele Carlani, founder of Progetto Katatexilux, an Italian studio that also produces multimedia exhibitions within the field of cultural heritage, tells The National virtual reality is becoming evermore important in terms of how we experience such historical monuments.

“Virtual reality is a mature technology but as a media tool it’s something completely new,” he says.

However, he points out that digitally interactive renditions of damaged, destroyed or unsafe sites must be accurate.

“My company is made up of archaeologists and art historians who are in constant conversation with scientific managers of the monuments to ensure the information transmitted is correct from a scientific point of view.”

Accuracy was one the biggest challenges Bashar faced when reconstructing the Mosul monuments.

Using a combination of blueprints, photography and drone footage — when safe to do so — was necessary, but finding accurate sources that depicted the original structures, proved more difficult.

Juan Aguilar, a digital archaeologist and PhD Student at the University of Luxembourg who has been periodically working in Mosul, specifically on Al Nabi Yunus Mosque, worked with Bashar and Qaf lab to source images and videos of that building from members of the public.

Bashar and Aguilar received hundreds of personal documents providing them with enough evidence to create historically accurate virtual reconstructions.

“Not only were we able to learn of additional architectural details of the mausoleum, but it was a beautiful example of how the public participated in the creation of cultural heritage content,” says Aguilar.

Professor Mohamed Gamal Abdelmonem, the chair of architecture at Nottingham Trent University whose research on digitising endangered cultural heritage sites won the Queen’s Anniversary Prize in November last year, is working on a similar project to preserve the heritage of Old Mosul.

Abdelmonem says Bashar's project is an important means counteracting the violent acts of extremist groups by preserving Mosul's legacy of ethnic and religious diversity and harmony.

However, he emphasises that while virtual reality is a critical learning resource, digitally reconstructed sites should not be seen as a replacement to their physical twin.

“What you get from a virtual and digital display is a simulative and curated experience for the public to engage with. It does not replace the original. It does however counter its deliberate erasure.”

The virtual reality exhibition at the Mosul Heritage Museum acts as both a digital archive of these historic sites and as a vehicle for public engagement and learning.

Yet, it is also marred with sadness.

“I knew so little about these heritage sites when they existed,” Bahsar says. “And after I learnt more about them, I thought, how did I not know that our city had this history and civilisation? I regret not visiting them when they were here.”

Bashar’s hope that these monuments may one day physically exist again is within the realm of possibility. The sites featured in the exhibition are at different stages of reconstruction through the aid of Unesco and other international partnerships.

For now, though, the virtual versions that Bashar and his team have created can stand as a source of inspiration and knowledge for the people of Mosul, and a link to a revered past that’s hard to forget.

“It's great when you see people using the headsets,” Bashar says. “We see their memories come back to them and it’s a good feeling.”