A new exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris explores Jewish history in the Middle East and North Africa, from antiquity to the present day.

Jews of the East (Juifs d'Orient: Une Histoire Plurimillenaire) is the largest exhibition of its kind to date, and is the first comprehensive show on Jewish history to be held at a cultural institution devoted to the Arab world. French President Emmanuel Macron attended the show's inauguration on Monday, praising its “journey across time and space”.

For more than three millennia, Jewish communities have coexisted with the region’s pre-Islamic societies and Islamic dynasties. “The ancient Jewish presence across the region is spectacular,” says historian Benjamin Stora, the exhibition’s curator and author of 2017 book Juifs, Musulmans: La Grande Separation (Jews, Muslims: the Great Divide). "There are early synagogues from Syria and an age-old presence in Saudi Arabia. I was surprised by the depth of this history."

Yet in recent decades, this history has been obscured by the tensions emanating from Palestine and Israel, which led to the migration of almost one million Jews. “I am often asked by students why Jews have left those countries. Was it the Arab-Israeli conflict? Was it decolonisation?” says Stora.

The exhibition, which runs until March 13, does not attempt to give these questions a simple answer. Instead, it aims to revive a vanishing collective memory.

A journey across time and space

More than 270 archaeological artefacts, costumes, crafts and photographs testify to this deep history. These include loans from major museums and private art collections in the UK, the US, France, Israel, Morocco and Spain.

The exhibition begins with artefacts from the Roman Empire, such as the sixth-century mosaic of a tree of paradise from the synagogue of Naro in Tunisia, but it also highlights the interactions between the Jewish and early pre-Islamic tribes of the Arabian Peninsula.

In the medieval Islamic courts, Jews contributed to intellectual and scientific thought, living as protected, but second-class, citizens. A 14th-century astrolabe with Hebraic inscriptions points to the flourishing Jewish culture in Al Andalus (now Spain), under Islamic rule.

In 1478, Spain’s Catholic monarchs sought the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. These communities dispersed across Europe and the Mediterranean, with many settling in Morocco and the Ottoman Empire. In Constantinople, Jews established early Hebrew printing presses.

Some of the most spectacular pieces in the exhibition originate from Morocco, where generations of Jewish craftsmen dominated artisanal trade. These include an ornate silver tiara with precious stones produced in Fes in the 1920s, and the image of a young bride from Rabat in the 1930s, dressed in fine silks with elaborate embroidery work.

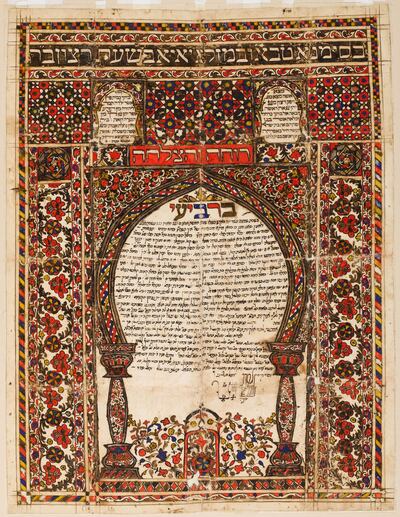

Collector William L Gross, who loaned objects to the exhibition, points to a Moroccan wedding certificate drafted in Hebrew in 1856. “It is illuminated with vivid colours, and the ornamentation is clearly inspired by the Islamic arts,” he says.

Under Ottoman rule and the European colonial mandate, urban Jewish families served as intermediaries between East and West. In the late 19th century, Algerian Jews were nationalised by the French Republic, leading to an anti-Semitic backlash in Europe, and growing local resentment in Algeria.

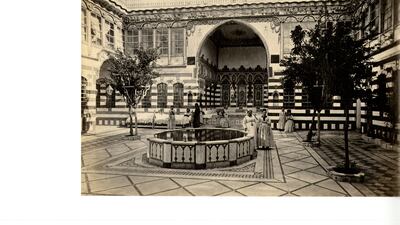

European Orientalist travellers, inspired by the painter Eugene Delacroix’s travels across Algeria and Morocco in 1832, came to document Jewish customs. A photograph by Ludovico Wolfgang Hart shows the formal dress and shoes of a young Jewish woman from Damascus.

There were also concerns that this distinctly local culture was beginning to fade. Urban Jewish families, influenced by the equality movements emanating from Europe, became increasingly secular. Illustrating this is the photograph of a wedding in the Algerian city of Constantine in the 1920s, which had caused a scandal at the time: Cecile Zerbibe, the daughter of a Jewish rabbi who married the Christian-born French officer Albert Gruson.

In the early 20th century, Jews and other non-Muslim communities continued to play a prominent role in Arab society, contributing to intellectual and political thought including Arab nationalism. One photograph taken in 1928 shows the Iraqi King Faisal II's ceremonial visit to a Jewish school in Basra.

This would change after the Second World War, resulting in the mass exodus of the region’s historic community. Contemporary artworks focus on the experience of exile and living memory. Director Talia Collis’s fashion film Yemenight (2020) portrays the henna ceremonies of Yemenite Jews. Meanwhile, Aaron Vincent Elkaim explores Morocco’s vanishing Jewish communities in his photo series A Co-Existence (2010).

In his statement about the series, Elkaim describes it as “a reminder that the sentiments of animosity and hatred prevalent today are shallower than they appear”.

Changing attitudes in France and abroad

The exhibition marks changing attitudes towards the official narratives on Jewish-Muslim relations. Today, a growing nostalgia for the Arab world’s Jewish communities is present in Iraq and Lebanon but also among France’s youth with North African origins.

“My students were often surprised to hear about the Jewish presence in North Africa,” says Stora. “Some had heard about it from their grandparents, but their parents were born in France and had never experienced it. They sensed that the collective memory was fading.”

It also sets a precedent for French colonial memory in North Africa. After Algeria’s declaration of independence in 1962, communities that were viewed as collaborators of the French were forced to flee. This included some 140,000 Algerian Jews, most of whom settled in France.

Yet their stories were obscured as the French defeat in Algeria was erased from France’s collective memory. For years, the Algerian War appeared as a footnote in French school curriculums. “As France forgot about the war in Algeria, so did the memory of Jewish communities there also vanish,” says Stora.

A recent revival of the Algerian War in French society has shed light on these forgotten communities, such as the European settlers known as the Pieds-Noirs and the Harkis, the Algerian Muslims who collaborated with the French colonial authorities. “But the way that European Pieds-Noirs will remember Algeria is different to the Jewish experience, because Algerian Jews had been there for much longer,” says Stora.

While an appetite is growing for this shared history among French Muslims and Jews, tensions remain between the two communities.

“It was important for us to hold such an exhibition in Paris, because France has the biggest Muslim and Jewish communities in Europe. Unfortunately a lot of stereotypes and prejudice exist between them, and there have also been confrontations,” says Stora. “The exhibition is not simply a cultural event but also a political one.”

Jews of the East (Juifs d'Orient: Une Histoire Plurimillenaire) at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris runs until Sunday, March 13