Nora Zeid’s Cairo is not entirely her own. It’s an amalgam of memories recounted by her grandmother and insights from various architects and heritage experts collected by the artist in an attempt to define the value of a city and its heritage.

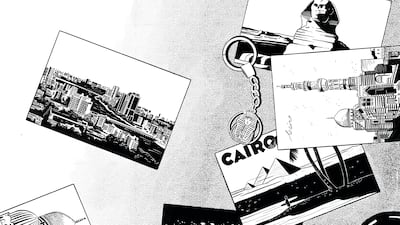

Her debut exhibition, Cairo Illustrated: Stories from Heliopolis, at Tashkeel in Dubai until Saturday, presents black-and-white illustrations of Egypt’s capital that turn away from the typical tourist sites. Instead, Zeid focuses on the quotidian lives of Cairenes, excavating histories of architecture and commenting on how sprawling urbanism has reshaped lives.

In Zeid’s work, memory is a material source. She constantly weaves her memories of Egypt's capital with research gleaned from interviews with architects such as Mahy Mourad, who teaches at The American University in Cairo, and Omniya Abdel Barr, an architect and heritage expert at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The body of work is the outcome of her participation in the Critical Practice Programme 2020 at Tashkeel, where she received mentorship and production support as part of the initiative.

Who is Nora Zeid?

Zeid was born in Cairo, but moved away when she was barely aged 3. She and her family relocated often when she was younger, living for years in Iran, Indonesia and the UAE. Though they lived abroad, they would visit Egypt every year.

It was her visit in 2017, she recalls, that changed her relationship with the city. Spending time with her grandmother in the suburb of Heliopolis, she saw how the residents of Cairo coped with its hustle and bustle. “She was able to have a pocketful of peace and quiet within the chaos,” Zeid says.

From there, she wanted to understand how the city had changed in decades past and how current developments were changing it again. “I was driven to understand Cairo, not cast judgment of it,” she says. “I stopped feeling alienated and started feeling inspired.”

Heliopolis and beyond

Her project Cairo Illustrated, which is also available as a published book, depicts scenes from Heliopolis, focusing on its architecture, streets, cultural centres and the commerce that thrives around the area.

Her choice of Heliopolis was personal – it was where she grew up – but also practical in terms of understanding how the city spread and its effects on the residents. The area was established in the early 1900s, with developments primarily led by Belgian industrialist Edouard Empain. It was intended for the elite, with Egyptian aristocracy filling the neighbourhood in the mid-1950s.

“It’s one of the first suburban neighbourhoods to be built outside of Cairo. It has since been swallowed by the city. It was marketed as a high-end luxurious, leisure neighbourhood, much like the ones that are being built outside of Cairo now,” Zeid says. “So this is a commentary about the city expanding and the infrastructure changing with it, and whether or not the modern heritage is being preserved.”

artist

In her research, the illustrator has dug up the origins of various neighbourhoods in Cairo, focusing on their modern heritage. One example is an illustrated memory from Abdel Barr, who grew up in Nasr City, close to Heliopolis. Zeid draws Abdel Barr’s story within the backdrop of the architectural history of the College du Sacre-Coeur in Heliopolis, a Catholic school built in neo-Islamic style.

“European architects built Heliopolis, so why does this school have neo-Islamic elements? Abdel Barr asked herself this and discovered that it’s a revival of Mamluk architecture that was reinterpreted by the architects. It is a kind of architectural continuity,” she says.

'I want to show the everyday Cairo'

Zeid’s work contains these everyday histories that are hidden and unknown in comparison to the grand narratives of Egypt’s ancient history. This difference is at the core of her work, questioning why certain histories and heritage are more prized, preserved and promoted than others. Her drawings of shopfronts and streets celebrate a part of Cairo that residents are more intimately familiar with, unlike the Pyramids of Giza, for example, that are not technically located within the city.

“I want to remove time as something that we use to define value for heritage,” Zeid says, explaining that even the way she has drawn the pedestrians in her urban scenes make them difficult to tie down to one time period. There are some dressed in contemporary fashion, others look like they are from the 1980s or 1940s.

With her work, Zeid attempts to capture a unique city that is confronting rapid change while trying to hold fast to its ancient history, not only as a form of heritage preservation, but as a strategic economic tool. What gets lost in this process? And what happens to cities when modern histories are forgotten?

“I want to show the everyday Cairo, the day-to-day life, the busy streets,” Zeid explains. “I make a comment on how, within this vast ancient history, the modern life and heritage gets lost. Everything after the 1930s, 1940s, our modern heritage gets lost and everything attached to it.”

Zeid’s use of personal histories and memories seems fitting here. The act of remembering could act as a powerful motivator for communities and authorities to recognise what needs to be saved, documented and preserved. Otherwise, without this resolve, memories of modern heritage will be all that's left.

Cairo Illustrated: Stories from Heliopolis is on view at Tashkeel until Saturday