For Kuwaiti artist Maitham Abdal art and politics shouldn’t mix.

“Politics has too many faces, which can get messy for an artist. By focusing on the human experience, I can achieve a greater message through my art,” he tells The National.

Yet this year, Abdal produced a series of sculptures about the displacement of Palestinians. The first, of a hand gripping a key, was on display at Al Hamra Mall in Kuwait City in May, as Palestinians were expelled from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood of Jerusalem.

“It’s an old hand, with lots of wrinkles. The key represents the homes of Palestinians before the occupation,” he says. “The work represents my objection to the injustice they have suffered for over 73 years.”

Then, in September, Abdal unveiled a new work dedicated to the six Palestinian prisoners who escaped from Gilboa Prison in Israel. The story of their escape made international headlines. “They used simple tools to reclaim their freedom,” he says.

But these works are an exception, he says. “I want to show humanity rather than political issues.”

Instead Abdal, a self-taught sculptor, devotes his time to creating figurative works using traditional and digital techniques. He is part of a new generation of Arab artists for whom the online world has been a source of learning, production and outreach. He taught himself sculpture by watching YouTube videos and relies on social media to promote his work. “I prefer to represent myself,” he says. “Galleries can get complicated.” His Instagram account has attracted more than 12,000 followers from all over the world.

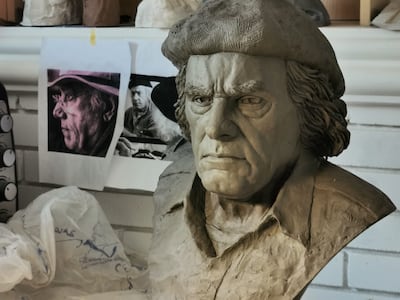

His influences range from the Italian Renaissance and European Impressionism to the hyper-modern world of Japanese anime. From his studio in Kuwait City, he shows me the bust of Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh, which he produced in resin using a digital modelling software and 3D printing. On the shelves behind him are models of famous anime superheroes. “As a child, I loved watching the dubbed anime cartoons that were broadcast in Kuwait and I’m a big fan of the director Hayao Miyazaki, and the ninja series Naruto,” he says.

Abdal was born into an artistic family and was often drawing and playing with clay as a child. His reluctance to engage in more political works is perhaps linked to his own experience of the First Gulf War in 1991 – when he was 6 years old. “After the war, there were paintings of Iraqi soldiers, of the Kuwaiti flag, and we used to draw a lot victory signs,” he says.

Later, he trained as an interior designer in Kuwait’s Basic Education College, working for many years as a draughtsman and designer. “But by 2012, I had reached a stage where I was bored of art and I couldn’t find the motivation to keep doing it,” he recalls.

He sought advice from his uncle, Kuwaiti artist and architect Fareed Abdal, who teaches at the University of Kuwait. “He told me, just follow your heart and see where it takes you. That was the moment when I realised that art belongs to the heart more than the mind,” Abdal says.

He began experimenting with sculpture. “I loved handling clay, the smell, the sensation of the water, the touch and the form. It was like therapy, where I could play and express myself,” he says. “I started exploring and looking for information that could develop my skills, practising, challenging myself and learning a lot. After years of experimenting, I got to the place where I could call myself a sculptor.”

Like an increasing number of young, self-taught artists, Abdal found an online community to support his learning curve. “I contacted lots of artists, especially when I messed things up,” he says. "Most of the time I got the answer I was looking for.”

More recently, he has devoted his work to the medium of digital sculpture, using software to draw and print 3D objects. “It’s like working with digital clay,” he says. “But I can undo any steps, at any stage of the process. You can print the file in 3D to any size, from 10 centimetres to 10 metres." Although he owns a 3D printer for prototyping, his larger works are produced at a factory in China and shipped to Kuwait.

Among his most famous digital portraits is that of Kuwaiti scientist Dr Saleh Al Ojairi. “He is a great man in Kuwait’s history,” he says. “Last year, I heard he was nearing his 100th birthday and I wanted to celebrate his work. I’m not sure how aware he was of my sculpture because of his advanced age, but his family reached out to thank me.”

He has also gained a following for his renderings of famous Japanese anime characters. “I get many requests for 3D models from followers in Japan. Now that anime is so international, there are many people who like to collect these models.”

By nurturing this online presence, Abdal can bypass some of the challenges affecting young artists in Kuwait. Although the country has long-standing galleries and an established art scene, exhibiting sculptures in public spaces, he explains, remains difficult. “For religious reasons, sculpture is [primarily] shown in private homes or galleries. There is no law against showing art in public spaces, yet these religious feelings still exist in our society,” he says.

Abdal hopes to use his online following to grow his sales. His digital sculptures can be reproduced in a smaller size for fans to purchase online. “Art sold in galleries is often very expensive,” he says, lamenting the art market’s inaccessibility. “But I have to offer something affordable as a gesture of gratitude to my audience who has always encouraged me.”