A new art exhibition in Uzbekistan is exploring the eastern foundations of modern-day algorithms and computation, showing how the work of a 9th-century polymath laid out the building blocks for our digital world.

Muhammad Al-Khwarizmi is today afflicted by the curious fate of being a lesser-known historical figure, yet having his name suffused as an eponym in everyday language. After all, the word “algorithm” was derived from the Latin translation of Al-Khwarizmi’s name and its increased recent use is a faint linguistic evidence of how seminal the contributions of the historic mathematician and father of algebra have been to the digital age.

Even so, Al-Khwarizmi is often an overlooked figure when tracing the developments of modern-day computing systems. Technology we take to be cutting-edge, such as robotic automation and artificial intelligence, is built on the same basic principles theorised by Al-Khwarizmi more than 1,000 years ago. Search engines, tailored streaming and shopping suggestions, as well as navigational services, are all part of a mathematical lineage that can be traced to Al-Khwarizmi’s treatises.

The exhibition Dixit Algorizmi, which opened on October 5 at The Centre for Contemporary Art Tashkent, aims to highlight the links of modern-day technology to the Persian polymath. The exhibition is curated by architect Joseph Grima with the support of co-curators Sheida Ghomashchi and Camilo Oliveira. It includes works from musicians, filmographers, architects, designers and theorists, as well as visual, conceptual and textile artists, all of which help give a cross-disciplinary view of the enigmatic historic figure and his works.

“The algorithm shapes all the possible interactions in modern culture through the apps on our smartphones. We know the word but we don’t understand it. Through the multisensory and illustrative exhibition, we are retracing its origin and the great impact it has had on societies and cultures, from ancient to modern times,” says Grima, an architect, curator and critic.

Speaking to The National, Grima points out that many of Al-Khwarizmi’s mathematical breakthroughs came as he pondered on better systems to help the public divide inheritances under Islamic law.

“Division of inheritance can actually be incredibly complicated to carry out correctly through a simple abacus, which was essentially the only instrument of mathematical calculations that existed in Al-Khwarizmi’s time,” Grima says. “So a lot of his work was inspired by the idea of making people’s lives better and easier.”

Born in the 8th century in what is now Uzbekistan, Al-Khwarizmi was one of the most influential scientific figures of the Islamic Golden Age. The Persian polymath was an astronomer and the head librarian at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad during the Abbasid rule, and published treatises that proved to be major contributions to mathematics, astronomy and geography. It was Al-Khwarizmi that put forth the concept of a zero as a number, opening a new realm of mathematical possibilities.

Among Al-Khwarizmi’s most famous mathematical works are the treatises On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals and The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, both of which were written around 820 CE. While the first treatise is credited with introducing the Hindu-Arabic numeral system to Europe, The Compendious Book is considered the first text to teach algebra for its own sake and was used as a principal textbook in European universities until the 16th century.

“The book was very influential,” Grima says. “It simplified lots of very tedious calculations and made them accessible to other people. More than 300 years after it was written, it was discovered by an English scholar living in Spain who translated it into Latin, which was the lingua franca of the science of Europe at the time, and [the book] became a transformative force in Europe.”

This original 1145 translation by Robert of Chester was given the title Dixit Algorizmi, from which the exhibition at The Centre for Contemporary Art Tashkent gets its name.

“Of course Algorizmi was a Latinisation of Al-Khwarizmi,” Grima says. “Because the whole of the book was essentially around this one idea of the algorithm, a mathematical approach to solving problems, the name of the author became synonymous with the thesis of the book.”

In the centuries-long process in which Latin was Anglicised, "algorizmi" morphed into "algorithm". However, it wasn’t until the late 19th century, as the first mechanical computers began to appear, that the word began seeing more frequent use.

“I become really obsessed with these lines across time and space that we use on a daily basis without really giving any thought to where their origins are,” Grima says. “In a way that’s a bit what the goal of the project is generally. To shine a light on this history.”

The works exhibited at Dixit Algorizmi are thematically linked to three different concepts, each of which provides a fresh perspective on the exhibition’s thesis.

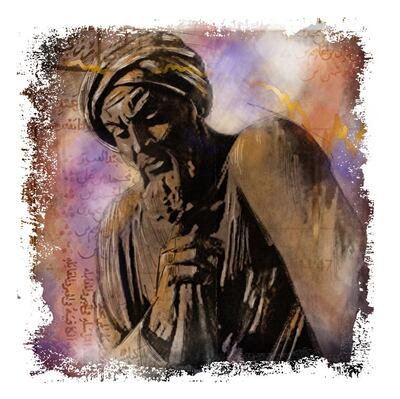

The first section explores the notion of the portrait and the representation of Al-Khwarizmi today, especially with the lack of reliable historical and biographical information. The resulting works are a series of commissioned collaborations between international artists and Uzbek craftspeople.

“If you Google search Al-Khwarizmi, you’ll get a few different generic faces of Middle Eastern men that don’t quite relate to each other. So the idea of the exhibition is also asking artists to recreate this mystic figure,” co-curator and architect Oliveira says.

As part of the research process, the curatorial team took several trips to Uzbekistan, meeting with craftspeople and commissioning works for the exhibition.

“Our first visit was in 2019. We visited all the major cities of crafts in Uzbekistan,” Ghomashchi, an artist and co-curator of Dixit Algorizmi, says. “We visited different artisans and their workshops.”

“Initially the plan was to invite a few artists to travel to Uzbekistan and find out what the figure of Al-Khwarizmi meant to people today,” she says. “Unfortunately, because of Covid-19, not a lot of people managed that. Two of our artists directly engaged with the craftspeople of different regions to create a contemporary work.”

The exhibition’s second section highlights the numerous ways in which the ideas first articulated by Al-Khwarizmi transformed our ability to interact with each other and our surroundings through technology. The third theme presents several redefinitions of our understanding of algorithms. On show are texts and diagrams in the form of posters contributed by international artists, writers and scholars whose work investigates the relationship between everyday life and the history of science and technology.

“Everyone was really bold considering the size of the team, which came together from all corners of the world,” Ghomashchi says. “This diversity and boldness is really rare to find these days in an exhibition. I love that about all the artists and exhibited works.”

Though the exhibition cannot be accessed virtually, Grima says there are plans for it to travel the world, with efforts under way to bring Dixit Algorizmi to the UAE. However, a public programme related to the exhibition, which features panel discussions as well as talks by Uzbek craftspeople, will be available online.

More information on Dixit Algorizmi and its programme can be found at www.ccat.uz