The foundations of Sneak Hotep’s calligraphy lie across the clandestine graffiti culture of Algiers and the customs of ancient Egypt.

The Algerian artist, whose real name is Ahmed Amine Aitouche, is showcasing a series of works at Dubai Calligraphy Biennale, which runs until the end of the month at Dubai Design District.

The broad parallel strokes and crescent-like curves of Hotep’s calligraphy fall across his canvases with varying hues of blue and gold. The works' play on shades exudes an illusion of depth, projecting letterforms from the two-dimensionality of the canvas.

The rigid straight lines portray influences from the early Kufic script, which was prominent between the seventh and 10th centuries. However, instead of running across the horizontal plane, Hotep pronounces the vertical in his work. His letters also have more prominent tails than those found in the Kufic script.

The colours in Hotep’s work are inspired by ancient Egyptian palettes and stones like the lapis lazuli which, though not particularly rare, was a symbol of luxury and the divine.

“For me, the shades of blue are the basics of my preferences,” he tells The National. “My inspiration comes from ancient Egypt, where they’d have these rocks from which they’d extract pigments of paint. The turquoise, the gold, the deep and lapis blues are colours that were prevalent in ancient Egypt. You could see them on ornaments and jewellery.”

The arcs in his strokes, meanwhile, are inspired by the khopesh, a curved ancient Egyptian dagger. The sickle-formed weapon dates back to at least 2,500 BC and was shaped to disarm opponents of their shields or to lock their arms. It is after this dagger that Hotep has named his unique calligraphic form.

“It was imported from Sumeria,” Sneak Hotep says. “It was used against Egyptians and they adopted it with time. First, it wasn’t used in war. It was a symbol of triumph. That’s how I use it. For me, the letter is stronger than the sword. The impact that writing has is more important than that of weapons."

Hotep has been making a name for himself as a calligrapher and street artist for the past decade, producing works all over the world, including Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Barcelona, Amsterdam, Madrid, Algiers and Paris.

He moved to Dubai six months ago but cut his teeth as an artist in 2005, tagging walls in the streets of Algiers when he was a teenager.

The artist’s two main influences are evident in his moniker. While Hotep comes from the ancient Egyptian term for "being at peace", the first half of his moniker alludes to his covert approach to producing graffiti in the Algerian capital. The process was a risky one and often resulted in him being apprehended by police.

“Graffiti was the way to express my freedom,” he says. “I was just tagging my name, Sneak, in the beginning. It was difficult to manage to do a simple tag. We’d have to spend nights in police stations and they always wanted to stick what I was doing to some political cause. They didn’t understand what I was doing. For them, expressing yourself on a wall was a political message.”

While his graffiti did not express discontent with any particular political entity in Algeria, Hotep says there is no denying there is an aspect to street art that is inherently political.

“Graffiti is political because you’re working against spaces used to brainwash people. I was seeing advertisements all over,” he says.

He adds that the advertisements made him realise that while there are those who share information in public spaces, there are also those who have something to say but don’t have the means to do it.

"They don’t have the money. With graffiti, you don’t have to have money to say something," he says, adding he could share his message for less than one dollar.

“There was nobody at the time doing graffiti,” he says. “The system was stronger than us because we were few. I started with my cousin when I was 13.

"We got some money for Eid Al Fitr. We went to the hardware store and picked some cans [of spray paint]. We bombed [tagged] a wall with our names. It ended up creating some noise in the neighbourhood. We liked that. I saw the impact of it.

"People were talking about it like it was an event. It was there that I realised what we could do with a simple spray.”

Hotep then began pursuing more formal avenues of expression, attending a fine arts school in Algeria to hone his craft as a calligrapher. Though he would still like to produce calligraphy in cities like New York and Bogota, for now, while living in Dubai, he is more keen on producing canvases and sculptural works that push the frontiers of calligraphy.

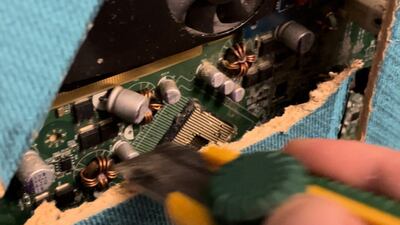

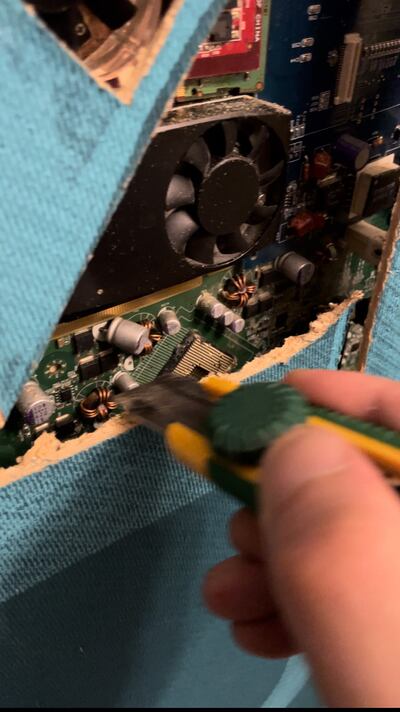

His intent is particularly noticeable with the installation Analepsis. A three-sided pillar of plywood adorned with his blue-hued letterforms, the piece is fitted with recycled motherboards at its centre, observable through gaps in the wood.

“I wanted to take calligraphy to another dimension,” he says. The art form, he says, is usually produced on a two-dimensional surface but he wanted it to be observable from multiple angles. Each of the sculpture’s three sides alludes to an aspect of time: past, present and future.

“Time is not linear,” he says. “I wanted to say that the aspects are not detached one from another. They come from the same essence, now.”

The inspiration for the piece came from an old cupboard in his grandfather’s house in Algeria. The family would store sentimental objects in the furniture piece, or “artefacts from our past. Objects that had emotional memories in them”.

The motherboards within the sculpture, which were supplied by Dubai Municipality, are meant to allude to the fact that most of our memories are now stored within computer chips and the cloud.

“Now we are counting on technology as a storage space to keep our memories,” he says. “Instead of cupboards, we are putting our memories in these chips. In the end, they will be thrown and they will be polluting [the environment].”

Participating in the inaugural Dubai Calligraphy Biennale has been an influential experience, Sneak Hotep says. The event has pushed him beyond his otherwise insular practice, connecting him with other artists and highlighting the range of possibilities within the art form.

“I don’t usually have time to see other artists’ works,” he says. “The platform permits artists to see other disciplines. I think this is very inspiring, the way they gathered us all on the same platform.”

Dubai Calligraphy Biennale runs across the city until October 31. More information is available at dubaicalligraphybiennale.com