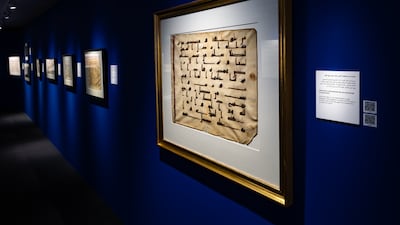

Sacred Words, Timeless Calligraphy, a new exhibition at the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilisation, is an opportunity to appreciate the practical and aesthetic evolution of the Arabic script.

The exhibition presents rare examples of Quran manuscripts and Islamic calligraphy that span 14 centuries and regions stretching from China to North Africa. The pieces stem from the private collection of UAE businessman Hamid Jafar and are being displayed for the first time.

The exhibition, which will be running at the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilisation until March 19, also coincides with the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Crescent Petroleum, the oil and gas company founded by Jafar in 1971.

“Mr Jafar's vision was to show how Islam was a unifying force and source of inspiration to so many different cultures and people, from the Middle East to China and India, to Spain and the Maghreb,” Entisar Al Obaidly, curator of Sharjah Islamic Museum of Civilisation, says. “Over 40 years, he has established one of the most important collections of rare Quranic manuscripts and calligraphy. These are the highlights.”

The exhibition is organised along three themes: the power of the written word of the Quran; the production of Quranic manuscripts across the Islamic world; and the beauty of the Quran as a book.

The first section of Sacred Words, Timeless Calligraphy emphasises the variations of the Kufic script. Most of the pieces were produced using vellum, which was meticulously prepared and polished prior to being written upon.

The opening piece, and one of the oldest in the exhibition, is a folio from a monumental 8th-century Quran manuscript. Presenting 12 lines of script on a landscape page, the folio was created in the central Islamic lands around the late Umayyad or early Abbasid era. It presents the 22nd chapter of the Quran, called Surah Al Hajj.

The script is evidently Arabic, but the lack of diacritics makes it a challenging, if not altogether illegible read for today’s reader. However, it is mesmerising all the same. The script features short vertical strokes and elongated horizontal lines that evoke a certain dynamism, as well as bends and loops that are more subtle than modern script forms.

curator, Sharjah Islamic Museum of Civilisation

“It is a fine example of Kufic script,” Al Obaidly says. “It is a powerful work and indicative of the calligrapher’s skill. The parchment was derived from animal hide and was not easy to write on.”

Elsewhere, a section from a 9th-century Quran manuscript shows the addition of red dots and succinct diagonal strokes along the Kufic script. The signs were added to aid pronunciation and recitation of the text. Green dots denote the letter hamzah and gold ornaments mark the end of each verse.

While the original script dates back to the Abbasid era, the gilt-leather binding is thought to have been added during the 17th century in the Ottoman Empire.

A series of joined folios of indigo-dyed parchment adorned with textured gold Kufic is one of the most eye-catching pieces. It represents a section of the Blue Quran, one of the most famous works of Arabic calligraphy, as well as the subject of much academic debate. A biofolium display shows the third and fourth chapters of the Quran, also known as Surah Al-Imran and Surah An-Nisa, in a gold that glints grainily under the display light.

“This biofolium is one of three that exist in the world,” Al Obaidly says. “Princes, kings and influential figures favoured these kinds of parchments because they were so rare and costly to make.”

As the Islamic world developed, so too did the Arabic script. The move from parchment to paper heralded the Kufic script’s progress into the New Style, otherwise known as Eastern Kufic. Thought to have been developed by the Persians, the script is made up of recognisable short strokes and upright long strokes.

With this, calligraphers moved away from landscape formats, opting to use vertical pages again. Better tools and techniques meant they could scribe more lines per page.

A good example of this is a paper bifolium from a 12th-century Quran made in Iran or Central Asia. The piece features nine lines of Eastern Kufic script on each page as well as diacritics, which make it easier to read.

Even easier to comprehend is the Muhaqqaq script. However, it was perhaps one of the hardest of the main six Arabic calligraphic scripts to master. Muhaqqaq was seen during the Mamluk era, but was gradually replaced in the Ottoman Empire by Thuluth and Naskh, and then Basmala.

A folio from a manuscript of the Five Suras is one of the finest examples of the Muhaqqaq script in the exhibition. Lofty vertical lines are juxtaposed by succinct horizontal strokes and sweeping arcs. The script is replete with diacritics and medallion-like ornamentation. The folio bears the 18th chapter of the Quran, Surah Al-Kahf, and was transcribed in Iraq or western Iran in the 14th century.

Nuanced and cursive details of the Muhaqqaq script are more apparent in one of the largest displays in the exhibition. A page from a monumental Quran measuring 186 centimetres in length and 119cm in width, looms with seven lines of script and gold embellishment.

The piece dates back to the turn of the 15th century and was created during the era of the Timurid Empire, which sprawled modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, South Caucuses, Pakistan, and parts of North India and Turkey.

The expansion of the Islamic world also brought in indigenous influences on the Arabic script and varying artistic sensibilities. The exhibition’s second and third sections showcase these diverse outputs.

One fascinating example is a Quran manuscript on paper that was created in the 19th century in the Sahel Region of what is today Bornu, Nigeria. Comprising 359 folios with 16 lines per page, the manuscript showcases the Sudani script, one of many in the Maghreb family of scripts. The page also features patterned designs that reflect the region's artistic motifs.

From China, comes large Quran manuscripts that were created during the era of Kangxi, the third emperor of the Qing Dynasty, who reigned from 1661 to 1722. One work features Sini (Chinese) script, and each volume contains 56 folios with five lines per page. It also has idiosyncratic floral and gilded illustrations.

A prayer rug dating to 1900 is another unique display in the Sacred Words, Timeless Calligraphy retrospective. Displayed at an angle, the rug features prayers inscribed as medallions, while the borders are adorned by Surah Al-Kursi.

“The centre features an arced design known as the Sultan’s Design,” Al Obaidly says. “It was woven in silk by an Armenian master weaver named Hagop Kapoudjian. We have also fitted a device called the Sound Shower above the spot from where visitors will be looking at the rug. A recitation of Surah Al-Kursi plays from the device, making visitors truly feel the Quranic verse.”

It's not all from days gone by, as technological elements have been embedded throughout the exhibition. There are QR codes beside all the works, containing information about each manuscript and artefact, plus several screens that magnify details of the diverse scripts and illuminations found on the manuscripts.

The exhibition ends with an educational component, with letter cards encouraging visitors to form the exhibition’s name in the different calligraphic scripts. A large three-piece turn box also helps juxtapose the illumination styles found across the Islamic world.

“Throughout the exhibition, we will have monthly programmes targeting different age groups that will inform participants about the history and development of Quranic manuscripts and Arabic calligraphy,” Al Obaidly says.

Sacred Words, Timeless Calligraphy: Highlights of Exceptional Calligraphy from the Hamid Jafar Quran Collection is ongoing at Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilisation until March 19