Over the past decade, some of the most glowing stars in the firmament of the art world have been Iranian - from Shirin Neshat, acclaimed since the late 1990s for her films, videos and photographs, to painters such as Farhad Moshiri and Charles Hussein Zenderoudi, whose work has fetched prices upwards of $1 million at recent auctions in Dubai. Buoyed by the West's growing fascination with all things Middle Eastern and the Gulf's flowering art market, the future for Iranian artists seems bright.

But until recently there was scant global buzz about prior generations of Iranian artists - none of whom, perhaps, seems more significant now than Ardeshir Mohassess, a prominent political caricaturist who many of today's successes count as a major inspiration. Ardeshir (as he preferred to call himself) rose to fame during the 1960s and 1970s, under the reign of Shah Mohammed-Reza Pahlavi, and was renowned for his deft and bitingly satirical drawings, which meld reportage with the conventions of Qajar portraiture and the flatness and decorativity of Persian miniatures. In his heyday, he was lionised by the Iranian intelligentsia and his work was broadly published. But after moving to New York in 1976, he gradually fell into obscurity.

All this changed two years ago, however, when the Asia Society in Manhattan presented a spectacular retrospective of his work. Called "Ardeshir Mohassess: Art and Satire in Iran", it was curated by Neshat and Nicky Nodjoumi, an Iranian-born artist who is also known for his own satirical paintings. The show presented the highlights of Ardeshir's career since his emigration, including Life in Iran (1976-78), a suite of intricate pen and ink drawings that focus on the atrocities perpetrated under the Shah's dictatorship. Reviews were universally glowing, with many writers comparing his work to the political caricatures produced by Honoré Daumier in 19th-century France or Francisco Goya's masterful series of etchings, The Disasters of War, made in the wake of Napoleon's Spanish campaign. In many ways, the timing was perfect: Iran was very much in the news - George W Bush had recently dubbed it "the world's leading state sponsor of terrorism" - and the market for Iranian art was starting to percolate. "We thought that for a man who lived most of his life in poverty, and unknown," says Neshat, "that it was the ideal moment for him to resurface." Indeed, although Ardeshir was too frail and too reclusive to attend his own opening, the attention worked its way into the market, and sales of his work began to pick up for the first time in years.

But on October 9, 2008, just two months after the show closed, Ardeshir suffered a heart attack and died on his way to hospital. What little money he had recently earned, Neshat says, went to pay for his funeral and burial. Neshat and Nodjoumi - along with Behrooz Moazami, a professor at Loyola University in New Orleans - were among those chosen by Ardeshir to run a foundation that will preserve and promote his achievements; they will mount another show in New York this autumn to commemorate the second anniversary of his death. (The foundation will use proceeds from sales of his work to help other artists in a similarly disadvantaged position.)

"At least he saw this glorious moment where he had this show," Neshat says, sadly. "I like to think that it's less sad because he had this opportunity for recognition. But he suffered so much, he really did." It wasn't always that way. Early on, Ardeshir's prowess and ambition seemed invincible. Born in 1938 in Rasht, the capital of Gilan province, he grew up in an intellectual, art-loving family. By the age of three, he was making artwork - his first painting is said to have depicted a confused-looking general -and by 12 or 13, his work was being published by the satirical journal Tawfiq. After a brief detour to study law and political science at Tehran University, he began contributing illustrations to Iranian publications, primarily the daily newspaper Kayhan. His enigmatic pictures, which often depicted surreally headless and limbless figures dressed in Qajari attire, seemed to be encoded references to the struggles that lay beneath the country's surface - not just during the Shah's dictatorship but those that had preceded it. Championed by the likes of the poet Ahmad Shamlu, he soon became an intellectual celebrity.

"He was always sort of a mythical character," Neshat says. "And because his work was printed in newspapers, it went above and beyond just art - the general public knew him, too." Unusually for a cartoonist, Ardeshir also showed his work in galleries. Nodjoumi, then an art student at Tehran University, remembers his first exhibition in 1967; it was held at Qandriz Gallery, co-founded by Mir-Hossein Mousavi - now the leader of Iran's opposition Green Movement, but then simply an architecture student. "You didn't see the original work," Nodjoumi says. "He blew it up in size, so the impact of it became like a painting. It was large, it was in your face, and it was realistic. It was very shocking."

Ardeshir also published his work in catalogues, which he sent to influential editors and intellectuals around the world. "He knew that was the only way to popularise his work," Nodjoumi says. By the early 1970s, he was also working regularly for the The New York Times; in 1974, those drawings were shown at both the Louvre and Columbia University in New York. As the story goes, Ardeshir was forced to leave Iran after his popularity piqued the interest of the Savak, Iran's fearsome intelligence agency, established with the help of the CIA. His editors were questioned and eventually his work was banned from their pages. But this, says Nodjoumi, only "boosted his popularity among intellectuals". Even after Ardeshir left Iran, he continued to have sold-out gallery shows there until the Revolution; once, Nodjoumi says, much of the work on display was purchased by the Shah's wife, the Empress Farah Pahlavi.

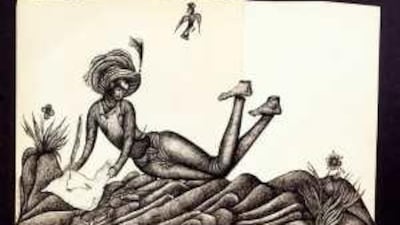

Nodjoumi believes that the real reason Ardeshir left Iran was to pursue his artistic ambitions: "He wanted to be recognised as one of the most powerful artists in his field," Nodjoumi says, "so in order to do it he had to come to New York." And after the Revolution, which came three years later, there was no going back. During his initial years in New York, Ardeshir published fairly widely, in journals like The Nation, Harper's and even Playboy. In America he began to address the depredations of the Shah's regime more frankly, as in "Life in Iran", his masterwork. In these drawings, people are usually whole but riddled with bullets, and the captions are bitterly sardonic. In one piece, a hanged man dangles from a gallows festooned with flowers as a bird sings overhead. The caption reads: "The convict's execution coincided with the king's birthday ceremonies."

Shortly after the series was completed, Ardeshir sold it to the Library of Congress, in a deal brokered by Ramsey Clark, the former US attorney general who had spent quite a bit of time in pre-revolutionary Iran protesting against the Shah. As Clark recalls it, the drawings fetched "a handsome sum" of something like $120,000. But Sara Willett Duke, a curator of popular and applied graphic art at the library, says that the price was considerably more modest: according to her records, Ardeshir received only $9,600 for 39 drawings - less than half their market value at the time.

Finding a steady income became increasingly difficult for Ardeshir. Apart from the fact that he wasn't at all talkative and never fully mastered English, his subject matter was something of a hard sell, especially after the 1980 hostage crisis. "The more powerful and richer American people supported the Shah and were particularly horrified by the Iranian Revolution," Clark observes. "And Ardeshir had become best known for his artwork portraying conditions in Iran under the Shah."

Nodjoumi says that Ardeshir was also ostracised by the rich and powerful Iranians who had fled to America after the fall of Pahlavi - many of whom had previously supported his work. "When the Revolution happened and he made his position clear, then those people who had been with the court, they boycotted him. They never bought work from him until recently, when we put up this show." Artistically speaking, Ardeshir's work was also out of step with the Minimalism and conceptualism of the era (although it would look quite au courant if he were making it today). Neither did it jibe with the tropes of American caricature. "His work is more of a narrative than a postage-stamp depiction of a moment in time, and it's more personal," says Duke. "If he were a young man working today he might be creating a graphic novel." But back then, she adds, "the graphic novel was still in its infancy.

Ardeshir's 1982 drawing, A Letter from Shiraz, portrays his situation succinctly: it depicts a turbaned man balancing carefully on a rock as he draws a picture of his own amputated feet. Life grew worse when, at 48, Ardeshir was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease, a degenerative disorder that made it hard for him to move, let alone make artwork. He kept at it anyway. When he could no longer handle his ink pen, he created increasingly shaky drawings with a felt-tipped marker or produced collages, like Matisse in his old age.

As time went on, some of Ardeshir's friends - who largely took over caring for him - tried to convince other Iranians to keep him alive by buying his drawings. Some went for as little as $200. "We couldn't say no," says Nodjoumi, clearly distressed by the situation, "because he needed the money". Today, according to the Iranian-born New York dealer Leila Taghinia-Milani Heller, whose gallery represented Ardeshir during the last year of his life, his later, shakier works might bring $5,000 to $10,000, while his early drawings have been sold on the secondary market for $30,000 and up (although little of this early work remains in the estate).

But at a time when Iranian artists are watching their work attract escalating prices and attention, many of Ardeshir's countrymen find his life, and his ardent pursuit of creative freedom despite the odds, inspiring. "Maybe the reason I went towards Ardeshir is that subconsciously I thought, 'We need to be reminded of the life he lived'", says Neshat, who got to know the ailing cartoonist at a time when she was mulling over her own artistic success.

"For me he was a symbol of the uncompromising intellectual who really believes in what he is doing," says Moazami. "He was persistent in his life, that was the most inspiring thing. All of us looked upon Ardeshir as part of our national heritage." Carol Kino writes about art for The New York Times and others.