By the time historian Lukasz Stanek arrived in Abu Dhabi in 2015, his research had led him on a journey of discovery through ramshackle archives across Eastern Europe, the US, Ghana, Nigeria and Kuwait.

An expert in the architectural history of the Eastern Bloc, Stanek was on the trail of a generation of largely anonymous, Soviet-era architects, planners and engineers who attempted to export a specifically socialist brand of building design from Eastern Europe to Africa, Asia and the Middle East at the height of the Cold War.

Although the work of this generation was largely forgotten, Stanek found traces of their often-disruptive legacy in buildings, streets, master plans and cityscapes in Accra and Lagos, Kuwait City and Baghdad. Their influence lived on in the vivid recollections of Middle Eastern and African architects and engineers who were taught by the socialists or worked alongside them in design and construction companies and on sites.

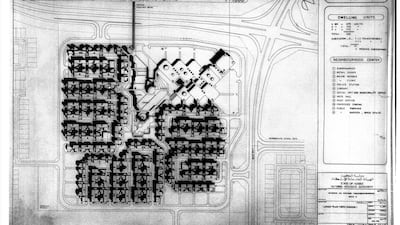

Planners and academics in Baghdad told Stanek about the Polish master plan devised for the city in the 1970s and an Iraqi architect, who now lives in Massachusetts, showed the historian plans for the Amiri Diwan complex in Kuwait City, designed in collaboration with Czechoslovakians. "I remember very well these Eastern European architects," an elderly Ghanaian architect said, recalling the 1960s in Accra. "It was the first and the last time that a white man had an African boss in Ghana."

Abu Dhabi's architecture: 'I don't know any other city where the contrast is so clear'

Stanek was drawn to Abu Dhabi, in part, by the work of the major Bulgarian state-owned architecture, engineering and construction company, Technoexportstroy, or TES, which designed a collection of prominent buildings in the emirate during the late 1970s and early 1980s at a pivotal moment in its urban development. What Stanek found when he walked around Abu Dhabi for the first time surprised him, even after several years of extensive research.

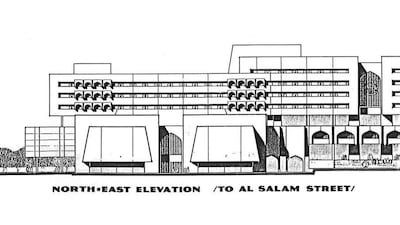

"There is such a powerful syntax between the very uniform but very tall buildings, and then within that verticality there are these horizontal lines," Stanek says. "The vertical lines stand for speculation and capital accumulation and the horizontal lines stand for religion, state and municipal power. That very clear contrast between the horizontals and the verticals – I don't know any other city where the contrast is so clear."

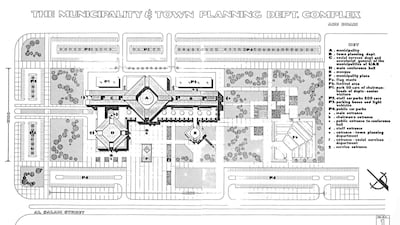

Nowhere did Stanek see this distinction more clearly than in the capital's city centre, where privately owned high-rise buildings still loom over the horizontal planes of public buildings such as the city's main bus station and the building housing Abu Dhabi Municipality and Town Planning Department building and the city's main bus station, both of which were designed by Bulgarian architects.

The Abu Dhabi Municipality and Town Planning building opened in 1985, the result of an architectural competition that launched in April 1979. It was won by Bulgarproject, the TES design office, and designed by Dimitar Bogdanov.

In a city where the urban grid is carefully defined and buildings appear to stand like exotic pieces on a chess board, each vying with the next for attention, Stanek says he sees an openness in Abu Dhabi's Municipality building and main bus station that not only represents an attempt to engage with the wider city on a strategic and a civic level, but that also echoes the structures' socialist origins.

"That certainly comes to the fore when you look at the other entries for the competition [to design the municipality building], most of which tried to create a compound and to work with the wall as a way of delineating the inside and the outside," Stanek says.

Bulgarproject has its headquarters in Sofia, but is responsible for infrastructure projects across West and North Africa and throughout the Middle East. It entered the competition in a joint venture with Tayeb Engineering, the Abu Dhabi practice of Sudanese architect Al Tayeb Rabei Abdul Kareem.

"By the late 1970s, such collaboration between actors from socialist countries and local firms in the UAE and Kuwait had become widespread, with professionals from Bulgaria, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia increasingly present on construction sites and in design offices in the Gulf," Stanek writes in his new book, Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War.

The 1984 law that obliged 'designs of public and private buildings to reflect Arab and Islamic character'

Highly qualified and often cheaper to employ than their western counterparts, design and construction professionals from the Eastern Bloc were an answer to the severe skills shortage in the rapidly growing cities of the region.

They could also draw upon a wealth of experience in the Arab world that extended back to the late 1950s.

This became particularly relevant in Abu Dhabi, Stanek writes, where an increasing number of clients, governmental or otherwise, were using regulations and competition briefs from the 1970s onwards to demand buildings that took context into account.

This impulse was even inscribed into law in 1984, when an Islamic Decree, signed by Sheikh Zayed, the Founding Father, obliged the municipality, city-planning and public works departments to ensure "the designs of public and private buildings and services premises … reflect the Arab, Islamic character and the history of the civilisation of the region".

As can be seen from the Abu Dhabi Municipality building, and the new municipality headquarters for Al Ain, the latter designed by Vasil Petrov of the Bulgarian state office Sofproekt, the result was architecture that combined a very Eastern European version of Modernism with regionally inspired details, decoration and motifs.

For Stanek, this desire for buildings and cities that displayed cultural as well as technological competence is a defining feature of Abu Dhabi's approach to urbanisation – one that first expressed itself in Sheikh Zayed's appointment of Egyptian Abdulrahman Makhlouf as director of town planning in 1968. "Makhlouf's master plan shows that on the announcement of the Municipality Building competition, there was nothing new in the juxtaposition of an enthusiasm for Abu Dhabi's growth and the desire to shape it according to an 'Arab-Islamic' tradition," the historian writes.

Rather than describing global urbanisation as a process that was visited upon societies in the developing world by western consultants, Stanek's history reveals the role played by socialist architects in constructing a negotiated future in which local rulers, authorities and communities took an active interest in shaping their own destinies.

Free from big-name architects and landmarks, Architecture in Global Socialism also gives voice to a largely forgotten body of professionals who travelled to the non-aligned world – neither communist nor pro-West – during the Cold War and whose lives and careers were enriched and globalised in the process.

“By the late 1970s and 1980s, exchange between Eastern Europe and the West existed – it’s not a question of absolute isolation – but there was a whole generation of architects from Eastern Europe who worked not only in the Gulf, but in the Middle East and North Africa more broadly, and for many of them that was a truly formative experience,” Stanek says.

He believes the architecture was political not in the way it promoted socialism, but in the way it became a part of the societies in which it was built. The architecture they produced may be difficult to love but it is all the more human for that, as is the history it illustrates.