Four late Mauritian artists, considered to be among the pillars of the country’s creative landscape, have been celebrated at the Mauritius International Art Fair (Miaf).

A Tribute to Our Late Artists took place at Moka’s Eureka House on Friday. It pays homage to the legacy of painters Roger Charoux, Vaco Baissac and Said Aniff Hossanee, as well as Tristan Breville, who is regarded as one of Mauritius’s most important photographers.

Family members were invited to speak at the event about the artists' legacies. The four were honoured in a ceremony that included Ameenah Gurib-Fakim, a politician and biodiversity scientist who served as the sixth president of Mauritius from 2015-2018. A short documentary film about the artists, produced by the Mauritius Broadcasting Corporation, was also screened.

“These are people who have honoured our Mauritian flag in the arts and culture scene across the world,” Zaahirah Muthy, director of Miaf and founder of its organising body ZeeArts, said in her welcoming speech. “These artists were part of our journey, part of Miaf in previous editions.”

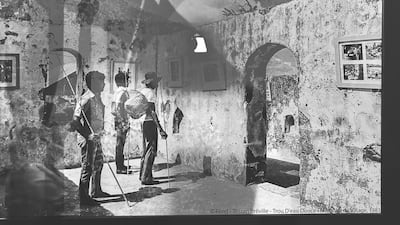

Works by the four artists were on display at Eureka House. A Creole wooden structure built in the early 19th century, the house stands by the Moka river. It has been refashioned as a museum and is a prime example of the architecture prevalent in the colonial period. With its historical significance, the building seems an apt venue to present the works of four Mauritian artistic greats.

Roger Charoux

With his vibrant colour palette and playful accentuation of forms, Charoux’s visual sense is unique and arresting. Among the works exhibited at Eureka House is The Green Chair, which presents its eponymous inanimate subject with overblown, circular features.

In Carpenters at Work, two craftspeople are hunched over what seems to be a table, their limbs arcing in visual harmony with their work. Meanwhile, in Roche Bois – named after an area in the Mauritian capital of Port Louis – a mother and her child are strolling along the street. A pack of dogs lay across the road, looking back at the viewer. A flock of birds flies down to perch on one of the neighbourhood’s colonial-era structures. The scene is painted with the vivid humour that is characteristic of Charoux’s work.

The painter, born in 1929, exhibited in most of the galleries and art venues in Mauritius. His work is also part of several national and international collections. Charoux died in June.

Charoux’s son, Bernard, says he shared a strong bond with his father, having shared similar artistic sensibilities.

“We lived in the same house and shared the same passion, the same trade,” he tells The National. “I am an interior designer and artist, so we were doing the same things together. Each time we went out, we would talk about architecture, art and interior design. It was something quite special.”

Aware of his father’s legacy, Bernard says he often feels his father looms over his work, despite his own successes. “It’s a big legacy, which I’ve been aware of more lately,” he says. “It's difficult to be the son of a well-known artist like this. Each one has got his own path. I've started to make my own name with my own clients. I have people that enjoy my work.”

Tristan Breville

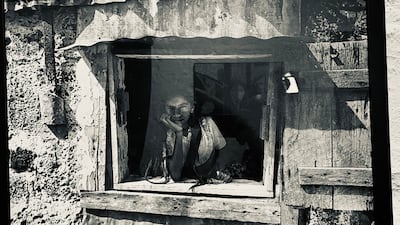

Few photographers have had as strong an impact on the Mauritian cultural scene as Breville. His work depicts everyday aspects of life in the country and serves as important documentation of its heritage and history. Breville died in March 2022, aged 76.

The works at Eureka House are testament to his photographic legacy, depicting Mauritians in villages across the country.

Breville was drawn to photography and visual media from an early age, his daughter Marie-Julie says.

“He started when he was seven or eight,” she says. “Even then, he was passionate about images. His happiness was when he was collecting, he would go through the bins of his neighbours looking for images and films. There was not a day he was not with his camera. He was [photographing] Mauritius every day. He was one of the biggest photographers of Mauritius, but he didn’t want to say that.”

In 1966, he also founded the Museum of Photography in Port Louis, which is now being run by his family.

“For him, the vision was to preserve the memory of his country,” Marie-Julie says. “My brother, mother and I run the museum now. We are only three people and it’s a huge, huge job. There are more than one million photography documents, and more than 1,000 cameras. It’s a sense of responsibility and pride. Maybe we don’t have enough funds, and that is a problem.”

Said Aniff Hossanee

Hossanee was another painter who approached the visual field with humour. Born in the Mauritian town of Curepipe in 1953, he began establishing himself in the country’s creative scene in his teens, before staging his first solo show at Max Boulle Art Gallery in 1969. He then moved to Paris to further develop his craft and often cited Francis Bacon and Pierre Soulages as inspirations. Hossanee died in April.

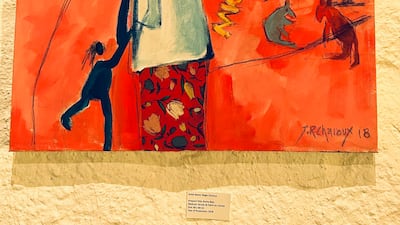

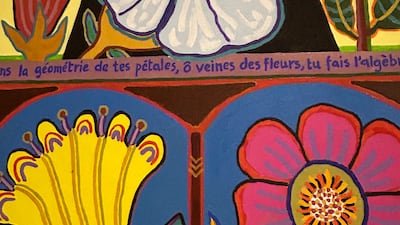

The two works displayed at Eureka House exhibit his unique approach to painting.

In Kites, triangular and square geometric patterns give the canvas an appearance of dynamic symmetry. Dans la geometrie de tes petals, meanwhile, shows his aptitude for taking everyday objects and flora and presenting them in ordered forms. The work is also an example of how Hossanee embeds texts within his painting. In this case, the work’s title.

Vaco Baissac

A painter who often represented Mauritius in international exhibitions, Baissac was born in 1940 and had his first show in 1980. Two years later he exhibited on Reunion Island before travelling to Paris and Brussels to pursue further education as an artist. He then made his way to Africa, developing his craft on the continent for two decades before returning to Mauritius in 1990.

Baissac sought to teach what he had learnt abroad to a new generation of artists. He established a painting workshop to inspire children and adults, while taking on several commissions across the island. He proudly identified as a Creole artist and saw the Mauritian Creole language as a linguistic testament to the country’s multifaceted culture. Baissac died in February.

Works by Baissac displayed at Eureka House exhibit his penchant for Cubist techniques, much of which were developed and inspired by traditional African arts. His Sleeping Dove features a woman lying on her back with a dove perched in her hand. His Au Soleil, on the other hand, is a portrait of a woman within a spectrum of orange that alludes to the many states of the sun.

“My dad moved back to Mauritius when I was 10 years old,” says Baissac’s daughter, Isabelle. “I was born in South Africa, and I would come visit him every year. It was interesting because I would see his progress every year.

“One day, he rang me and said, 'You know what, I’m just going to do art. I’m not going to do anything else. I'm not going to work and do any other job.' He used to own restaurants. He used to do a lot of other things. It was a leap of faith. He believed in what he did and what he was,” Isabelle says.

When she next travelled to Mauritius to visit him, Isabelle noticed a marked change in her father’s demeanour.

“He had developed into somebody just coming into their own and seeing everything the way that they wanted to and being really content with that,” she says. “I was in my late teens, and that is a difficult age for anyone. It was just wonderful to have that role model that was somebody that was just sure of himself.”