The largest district in India, Kutch in Gujarat occupies a unique position; straddling not only the borders of India and Pakistan, but the sea, too. As a centre of cultural exchange, it has spawned some fascinating crafts, many of which still survive to this day.

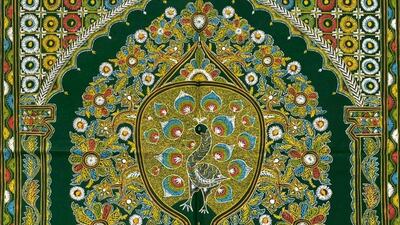

A six-inch 'kalam' pen in hand, Mohammed Jabbar Khatri retraces the outline he’s drawn on a piece of cloth. The design draws from the Tree of Life, an archetype prominent in many mythological, religious and philosophical traditions across the world.

At his side is a dabba, similar to the traditional Indian masala box, where the spices make way for globs of putty-like natural paint formulated by boiling castor oil over days and adding pigment.

He dips the old iron stylus into the paint, adding strokes to his design with a flourish that only comes from years of practice. His fingers dance as the stylus swirls continuously without touching the fabric. When he finally stops, his free-hand flourishes have created an intricate, needlework-like pattern.

Jabbar belongs to the Khatri family, the last in Gujarat's district of Kutch to practise the dying art of rogan painting. For over eight generations, the Khatri family of Nirona village has single-handedly kept this art alive.

“Rogan art is believed to have originated in Persia about 300 years ago. Rogan translates as oil in Persian and the art was traditionally used to embellish bridal trousseaus,” Jabbar says.

He explains the process in detail: castor oil is boiled vigorously until it transforms into a gelatinous substance on cooling. Natural colours are then blended in using the sil batta, traditionally used in Indian homes for grinding spice mixes. The colours are used to make wall hangings and tapestries, curtains, sarees, table cloths, and skirt borders.

Rogan art was once the only source of livelihood for the Khatris of Nirona, says Abdul Gafur Khatri, a master artisan locally known as Gafurbhai.

“Local communities used these fabrics to make ceremonial clothing, ghaghra-choli (a type of clothing), bedcovers, and more,” he says. The designs, usually geometric or floral, are extremely labour-intensive: smaller works take about four to five days, but intricate work on sarees can take up to six months.

The proliferation of machine-made industrial textiles after the 1960s sounded the death-knell for rogan painting. Locals shifted to cheaper mill-made and synthetic fabrics and, by the 1980s, not many were interested in buying or creating rogan art.

Gafurbhai, like many other villagers, headed to Mumbai to find work. He returned in 1984 after his grandfather wrote to him, exhorting him to carry on the family legacy. But it wasn’t easy. The family struggled to make ends meet for years.

Things changed family after Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 gifted a rogan painting depicting the Tree of Life to then US President Barack Obama. Following this, Gafurbhai went on to participate in many exhibitions and workshops across the world, and was awarded the Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian award, in 2019.

A capital of crafts

Rogan art has put Nirona on the tourist map, with domestic and foreign visitors flocking to it, seeking live demonstrations. But the village is also renowned for two other crafts: lacquerwork and leatherwork.

Lac, the resinous secretion of numerous species of lac insects, has also been used in Indian craft for centuries. Ancient India and its neighbours used it as wood finish, skin cosmetic and lacquerware, as well as for dying wool, silk and leather.

The Vadhas, a nomadic community that migrated from beyond Sindh before the partitionof India, brought with them the art of lacquerwork. Historically, they gathered natural stones and colours from forests and used them to craft lacquer goods that they traded with the cattle-rearing Maldhari community for dairy products.

Today, a few families in Nirona make lacquer items, mainly for use in the kitchen. These include colourful spoons, spatulas, rolling pins and boards.

Lalji Vadha Mala, a craftsman following in the path of his ancestors, explains: “Lac is heated until it becomes pliable, kneaded with colour and made into thin sticks. The wooden article is smoothened, and put on a lathe and rotated while the lac sticks are pressed into position. The friction softens the lac and spreads it over the wooden item."

In a small workshop nearby, Devji Poonja is hard at work on a piece of leather. Leather craft was traditionally used to make harnesses for camels and horses, footwear, musical instruments and storage containers.

Modern craftsmen apply their craft to lifestyle products such as chappals (sandals), juttis (shoes), phone covers, bags, mirrors and lampshades. The leather is often used in its natural state but many craftsmen now use dyes in shades of brown, red, maroon, and even yellow and blue.

“We use punches of different shapes and sizes to make holes in the leather and create geometric patterns like circles, triangles, squares, and ovals, or other shapes like leaves, hearts, moon and stars,” Poonja says.

Poonja says men usually work on cutting, punching, shaping and joining the leather pieces, while women add embellishments such as contrasting embroidery and mirror work.

Building bridges

Across Kutch, craft forms abound, thriving at the intersection of culture and community. Kachchh, as it was known earlier, had vast land and sea trade relations with the Swat Valley, Africa and the Middle East. The border state shared a river system with Sindh and Rajasthan, and its continuous exposure and absorption of cultures from different regions shaped its cultural identity.

The tough climate pushed communities to constantly innovate with material and textile crafts to add colour and verve to their lives, creating the forms now synonymous with the border state.

Hammering, forging and casting all kinds of metal – iron, silver, copper, and other alloys – also plays a crucial part in the history of Kutch. Across the state, craftsmen churn out utensils, ornaments, and silver jewellery. In Bhuj, however, many focus on copper bells.

Copper bells came to Kutch with the Lohar community of Sindh, now in Pakistan. Even today, many villages near the India-Pakistan border area make copper bells for cattle.

Ramzan Lohar, who has a metalworking workshop in Bhuj, says the process is simple: a small piece of copper is beaten with a hammer and then shaped into bells. “What sets our ghantadi (bells) apart is the fact that they use no welding or nails; we use a unique interlocking system,” he says.

More than 10 generations of Lohars have been making bells, he says, adding that they are now made in up to 13 sizes and customised – with sounds and notes - for different animals. Priced between Rs 50 (Dh2) and Rs 2,500 (Dh111), they make an attractive buy now that they have been fashioned into windchimes, says Anas Lohar, Ramzan’s son.

About 72km from Bhuj, Khavda, known for its maati no kaam bowls, traces the history of its pottery to the Indus Valley Civilisation. Over centuries, the region's Kumbhars (potters) have developed their own distinct style. Now, they fashion a range of utility products, including pots, plates, griddles, bowls, and boxes.

“We use the rann ki mitti (a type of mud). Men shape the utensils on the potter’s wheel and let them dry in the shade after which the women use natural red, black, and white colours to decorate each piece with beautiful designs,” Abdullah Kumbhar says. The pieces are then baked in a furnace and given a thin wash of geru powder.

In olden days, Kumbhars were prosperous, supplying all the earthenware households needed for daily use and special occasions. Their downslide started as indigenous steel products and cheaper Chinese items gained in popularity.

Today, Kumbhar, his wife Rahimaben, and their family say they are the only ones in Khavda keeping this age-old craft alive. A recent interest in all things natural and handmade has led to a resurgence in demand, and their work is now available online and at select artisianal stores across India.

Over decades, Kutch’s rich crafting heritage has been driven by indigenous skills, and fuelled by the merging Hindu and Islamic cross-cultural traditions. International influences, courtesy of its coastal location, have also had a role to play. The motley mix of locals, immigrants, traders, and explorers married their skills and traditions, creating a vibrant kaleidoscope of arts and crafts.