Seated in one of the corners of the upper-floor hall in a building on the Indian side of Kashmir is Ghulam Mohammad Zaz.

Even though he's 80, he can still meticulously prepare a santoor, a musical instrument with origins in Iran, for a client residing in Australia.

“Our family has been renowned for making traditional musical instruments for centuries,” Zaz tells The National. “I inherited the art of pouring music into wood and strings from my grandfather initially and later from my father.”

Playing the right tune for decades

For more than five decades, Zaz has carried on the legacy of his forefathers, dedicated to contributing to a society with a profound history of producing culturally rich music.

“There is no one left in Kashmir who knows how to make or repair the traditional musical instruments like santoors, rababs and sarods,” Zaz says. “People from different parts of the world such as Germany, Italy, France, England etc have purchased different kinds of instruments from me.”.

Throughout his 50-year career, Zaz use to make instruments from precious materials like Kashmiri stag antlers before the local government imposed a ban on hunting due to the rapid decline in their population.

“Such musical instruments are no longer available due to a strict ban on the sale and purchase of the materials,” he says. “Even if the materials were available, people would find it difficult to obtain due to their high price.”.

In the past couple of years, he has reduced the production of instruments, citing age and poor eyesight. He says that manufacturing handmade santoor, rabbab and sarod is a “time-consuming process and usually takes months to complete one piece”.

Zaz also says he does not have a successor, meaning the skill he has will likely end along with him.

“I have no son but three daughters, therefore, none of my family members will carry on our ancestral profession to future generations,” Zaz says. “Neither my brothers, cousins nor their children learnt the art of making traditional musical instruments as they pursued careers in different professions.”

Business no longer comes up smelling of roses

The Indian side of Kashmir has been a hub for skilled craftsmen since the arrival of Islam in the 14th century. However, due to a lack of artisans, many of the crafts are at risk of disappearing.

Abdul Aziz Kozgar, 65, patiently waits for customers in his wooden shop located in the Khanyar locality of Srinagar. The store is decorated with a collection of vintage jars and bottles, varying in sizes, creating a charming atmosphere inside with origins dating back to the Ottoman Empire.

Kozgar says he is the last man in his region to extract rose water using ancient techniques. He purchases rose petals and boils them along with other herbs in a cauldron before the vapours travel through coils where they are condensed and distilled.

“I am running this shop as a tribute to my forefathers. I was initially associated with this profession on a part-time basis but later on, I joined the family business completely,” says Kozgar. “The instruments, bottles and jars are centuries old after being imported from countries like Spain and Germany.”

shop owner

Kozgar's family used to make herbal medicines and syrups to treat several ailments. However, recently, they have focused solely on selling rose water as the demand for syrups and herbal medicines has declined with the emergence of modern medicine.

“Today, most rose water is purchased by caretakers of shrines so that they can sprinkle it on the devotees during religious gatherings,” he says.

Kozgar says he does not make enough money by selling his product but adds that social media has greatly helped increase interest.

“Tourists from different parts of India and abroad come and purchase rose water from me,” he says, adding how one bottle costs 40 rupees (50 cents).

Kozgar says he will not force his children to carry on his profession.

“I do not know what will happen to these precious jars after me but as long alive this shop will remain functional,” he adds. “My children know how to make rose water as I have trained them, as I was trained by my father, but to carry forward this legacy would be their own choice.”.

'I refuse to turn my back on my craft'

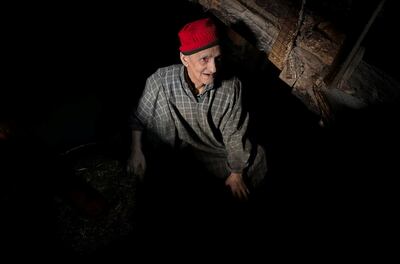

Ghulam Ahmed Wani, 82, is one of the last individuals of his kind who operates an ox-driven oil mill in the Pampore neighbourhood of Pulwama district in south Kashmir.

Pampore is also known as the saffron town of the region. According to Wani, the last decade has seen a decline in ox-driven oil mills because of the low income from it.

“I am unsure how much longer I will be able to operate this mustard oil mill, as my time is limited,” says Wani. “I have been associated with this profession since my childhood. For a brief period, I worked as a labourer, but I soon discontinued it as my passion lay in my own craft.”.

Wani says none of his descendants are willing to continue because there is hardly enough demand for manually extracted mustard oil with people purchasing branded oil from the market instead. He says people mostly use the oil for massaging for relaxation and to relieve tension. Some will use it for cooking but it is more expensive than what can be found in shops.

“On many occasions, my family insisted on discontinuing this profession, but I refused, telling them that if I manage to make a hundred or two hundred rupees [$3] a day, it would be sufficient for me,” Wani says.