On a hot August Saturday, the speed limit at the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve is 30kph. To the right, a Dodge minivan leads a Toyota Yaris and an ageing Chevrolet as they vie for parking spots closest to the public beach. To the left, cyclists and roller skaters weave between one another, doing laps around the 4.3km track. Except for the fleeting sound of a car stereo, it's quiet and peaceful - two words rarely paired with the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve, the home of the Canadian Grand Prix.

Every year for nearly 30 years, exercise enthusiasts in Montreal, Quebec, were kicked off the track during the first weekend of June for the race, one of 17 in the Formula One Championship. They were replaced by 20 finely tuned cars, manned by the world's most skilled drivers. The circuit - carved on the man-made Ile Notre-Dame in the St Lawrence river - overflowed with fans watching racers reach speeds of up to 325kph. Some 300,000 would come to the island during the three-day race, and up to 50 million more would watch on television.

For one weekend a year, Montreal felt like the sporting capital of the world.

Then, rather unceremoniously, it came to an end. In October 2008, after Montreal organisers and Bernie Ecclestone, F1's commercial rights holder, failed to reach an agreement on race fees, the race was cancelled.

And so on the first weekend in June, the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve looked much as it does today, the quiet clacking of bicycle gears replacing the shrieking of F1 engines.

The Ferraris, the McLarens and the Renaults were instead racing in Turkey, and a new Grand Prix in Abu Dhabi had been added to fill the hole.

And while the capital set to work preparing for its first Grand Prix ever on November 1, Montrealers were left wondering how they lost their race.

Now that Ecclestone has put the Canadian Grand Prix back on the provisional 2010 calendar, they grapple with what it still means to them.

The Canadian Grand Prix began in 1961, and for 16 years, it switched between the circuit at Mont Tremblant, a ski resort north-west of Montreal, and Mosport International Raceway in Ontario. It wasn't until the race moved in 1978 to Montreal that it took off.

And while there would be many memorable moments at the track - local hero Jacques Villeneuve crashing into the "Welcome to Quebec" banner in 1999, the Schumacher brothers finishing first and second in 2001, Lewis Hamilton winning his first Grand Prix in 2007 - nothing compared to the first race.

It took place on Thanksgiving weekend, October 8, 1978. Snow fell in the morning and by race time, patches of white had mixed with mud surrounding the track.

"It's bitterly, bitterly cold for the competitors," the BBC announcer Murray Walker said. "And a crowd of 100,000 Canadians here are rooting for one man, the man in the red car there, number 12, Gilles Villeneuve."

At the time, the track was called Circuit Ile Notre-Dame. It would not be named after Villeneueve until his untimely death during a race in 1982.

In 1978, Villeneuve was still the French-speaking province's first racing superstar. But at the beginning of the race, he was positioned in third place, behind Jean-Pierre Jarier and Jody Scheckter. Early in the race, Villeneuve slipped back into fourth, but fought back and passed Alan Jones and Scheckter to second place, where it looked as if he would stay. With a 21-second lead after 21 laps, Jarier seemed unbeatable. But then he unexpectedly pulled out of the race on the 47th lap with an engine problem. Villeneuve inherited the lead and cruised to victory.

"Villeneuve wins!" Walker exclaimed. "And 100,000 cheering Canadians went wild with delight at the first ever Grand Prix win by a Canadian in, of all places, Canada. It's Gilles's day without a doubt."

But it was more than Gilles's day; it was Montreal's, too. And it marked the beginning of the city's obsession with Formula One.

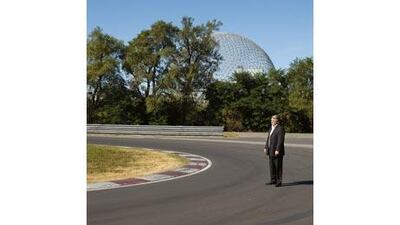

"It was almost too good to be true," says Roger Peart, who designed the circuit and is now the Canadian delegate to the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), which oversees F1. "People have asked me many times how I managed to fix it so he could win."

Normand Legault, whose name would later become synonymous with Grand Prix in Montreal, was also amazed. "Gilles won his very first race of the very first Grand Prix. It was love at first sight," he says. At the time, Legault was a young business marketing student from Université de Sherbrooke. He had been picked by Labatt Breweries to help organise the first Grand Prix in Montreal, which the company sponsored. "We didn't know what we were doing," Legault says. "Before 1978, Quebec fans didn't know an F1 car from a snowmobile."

But with Villeneuve's victory and the subsequent media hype, everyone realised, as he says, "Maybe this is fertile ground for this."

In 1981, when he was only 25, Legault was made general manager of the race. With this promotion began his relationship with Bernie Ecclestone, then the CEO of the Formula One Constructors' Association and owner of the Brabham team. Legault managed the race for two years, then left to start a graphic design company. He returned in 1989, at Ecclestone's request.

In the meantime, the Grand Prix had been cancelled in 1987 over a sponsorship dispute between Labatt and their rival brewery, Molson.

Despite the hiatus, the race was still popular, and Legault eventually bought the Canadian Grand Prix in 1996 from Molson. Under his leadership as a general manager and owner, the Grand Prix quickly became a highlight of the F1 calendar. Legault pegs the success first and foremost to the Villeneuve family. It's a sentiment shared by Max Bitton, a local racing enthusiast.

"Gilles Villeneuve is a racing icon," Bitton says. "When he died, it was like Quebec lost his son."

Gilles's son, Jacques, continued the family tradition by becoming an accomplished driver himself. In 1997 he won the F1 Championship and is still racing stock cars today. Beyond the Villeneuves, though, is Montreal itself.

Sometimes called "Paris in North America", Montreal is the largest Francophone city in the world after the French capital. Old Montreal, a cobble-stoned district across the river from Ile Notre-Dame, could fill in for an old town centre anywhere in Europe. It's even nicer in the summer, and in 1982, the Grand Prix moved from the end of September to the first weekend in June. Now tied to the beginning of summer, The Grand Prix became an event for the entire city.

Most notably, Crescent Street would close down for three days to host a party. The street, just off the main drag of Rue St Catherine, is a strip of bars and nightclubs - including Jacques Villeneuve's New Town restaurant. In 2008, an estimated 500,000 people crowded into Crescent Street over a weekend filled with live music, celebrity appearances and much eating and drinking.

"You don't need to be attending the race per se, to be part of the Grand Prix spirit," explains Legault, adding that for some, "the race was just an excuse to go out partying."

The Grand Prix was estimated to bring in 75 million Canadian dollars a year (Dh 276 million), much of which came from international tourists. In 2008, 7,000-8,000 fans came from Europe, 15,000 from the United States and about 3,000 travelled from Japan. Once everyone arrived, they found access to the circuit easy: it's just a couple of metro stops from downtown.

"How many cities in the world can you say I am going to take the subway to get to the track?" Legault asks. And while the track itself wasn't the drivers' favourite, its compact design allowed fans to get up close to the race.

"You can see the drivers shifting at the hairpin turn," Legault says. "They want to hear the roar of the engines. The hair on their arms will stand up just from listening? there is a lot of user friendliness for fans. After all, isn't that who we do this for?"

The first indication that Montreal might lose its popular Grand Prix came in 2003. That year the government passed a law banning tobacco advertising, a cornerstone of F1 teams' financial gains. Ecclestone, as a result, threatened to cancel the race unless there was some form of compensation for the CAD$29 million (Dh9.7 million) in lost revenue. At the time, he also criticised the circuit, saying it was in need of significant repairs.

The crisis was averted only when the provincial and federal governments offered CAD$6 million (Dh22 million) each. The fact that Ecclestone seemed so willing to drop the race frightened local fans.

Bitton says he soon realised that the race's demise would be "inevitable". And his fears were confirmed on October 7, 2008, when the FIA released its 2009 schedule.

The news sent the city into a brief state of shock, then anger, when it came out that the cancellation had been triggered by a dispute over money. As Michel Flageole, who runs Flagworld, a popular news and photography website from Laval, Quebec, says, "We did not understand why Bernie would ask so much money for a race that was so successful, so loved. We just did not understand." Ecclestone's asking price was reportedly CAD$31 million, and Canadian newspapers took aim at the British billionaire. "He became the official devil of the city," Flageole says. "Every paper, every report - nothing positive came out on Bernie."

Dean McNulty, writing for Sun newspapers in Canada, pointed out that "Legault had a contract with Formula One Management - Ecclestone's promotional and financial arm - that gave Montreal the rights to the Canadian GP through 2010. "Turns out contracts with the diminutive Briton are like putting in an offer on a new house - it's good only until some one else comes along with a better deal."

Their anger, in many ways, was understandable.

"It was huge. It was a very, very popular event," Peart says, adding he was surprised by the decision. "It was one of the few Grand Prix that sold out. Literally sold out."

Legault, who was in Europe at the time, was silent at first. Sitting in his office nearly a year later, he reveals he had been in the midst of negotiating race fees with Ecclestone. The cancellation, he says, was a hardball play that took him by surprise. Legault called Ecclestone's bluff, arguing that F1 is now no longer affordable for a private enterprise. A businessman, Legault concluded, would be forced to pass the cost on to sponsors or ticket buyers, both who have their limits - especially in a recession. "In today's environment, they'll say: 'No way'."

So he decided to retire, refusing to seek government support. "I'm not the minister of tourism," he says. "My mission is not that the world discovers Montreal. My job is to put a race together."

The government did jump in to save the drowning race. Less than two weeks after the Grand Prix was cancelled, three representatives from the federal, provincial and municipal branches flew to London to meet Ecclestone. During discussions, the government offered CAD$110 million over five years, but Ecclestone insisted on CAD$175 million for five years, and the government backed away.

The race, it became clear, wasn't going to happen in 2009 - and potentially ever again.

At 26, after a car accident ended Max Bitton's dreams of being a racing driver, he decided to begin selling F1 merchandise. He had realised that no one in Montreal had the rights to sell Ferrari gear, and so he flew to London and approached the company responsible for F1's licensing. At first, they turned him away - so he came back with investors and a business plan. Now, he runs a 60sq m store, F1 Boutique Canada, in the Old Montreal neighbourhood. As he gives me a tour of the shop, he points out the back half is being turned into a Nascar section. There is a Nascar race coming up in two weeks - at the end of August - and he wants to boost sales. Still, he likes to show off his CAD$1,000 motorised toy Ferraris in the front window, and says he is working on bringing Ferrari bicycles to Canada. He also sells race-worn drivers' clothes, including a Michael Schumacher jacket.

On the way to last years race, Bitton was one of many fans waiting for the first train early in the morning. Once there, he'd set up booths selling F1 merchandise. For him, it was the best time of the year.

"In Montreal, you are in a cross-cultural type of environment. You have European flair. You have American marketing power. You are between Milan, New York and Paris. It's like? wow."

With the Grand Prix's cancellation Bitton says he's had a 50 per cent drop in sales this year. He's opened a restaurant facing the scenic Old Port to compensate. "I was very, very sorrowed and not just on a financial level," Bitton says, explaining he hires family members and 75 students each summer for the race.

To help lobby for the race's return, Bitton formed a Facebook group. In fact, he had to create multiple Facebook groups, because the social networking site only allows 5,000 members per group. He says he heard from everyone, from doctors to firefighters, who were upset. "This is an insult to the memory and legacy of Gilles Villeneuve," one user wrote on the site.

Bitton summarises the disappointment succinctly: "It was a way of life in Montreal. The Grand Prix comes with the sun, and when it comes it's time to party."

For Sandy Greene, the party used to start in January, when she began securing licences and equipment for Crescent Street's bash. Greene is the director of the Crescent Street Merchants Association, one of the groups hardest hit by the Grand Prix departure. The Crescent street festival had become "the largest outdoor event in North America", Greene brags, and she would rent a nearby hotel room so she could be on site every morning at 5am. "I pretty much used it just to bathe," she says.

For three days she had to make sure the city, fans and car companies were happy - a difficult balancing act.

But this year she didn't welcome the break. "It was the most devastating news for the association. And it made my job much more difficult."

The merchants, she says, made about four times as much during the Grand Prix compared to a normal summer weekend. So she had to try to find something to fill the void. The vendors originally thought about holding a Grand Prix party regardless, but "we thought 'Does that present a shrinking image of Crescent Street?'". Instead, they held a large party to celebrate the street's 50th anniversary. Many people came out, Greene says. But while it was fun, "there is no way of replacing Grand Prix? nothing could fill the void".

Even when rumours began circulating in August that the race would come back, Greene was only "cautiously optimistic". She says some damage is irreversible. The street lost a few dépanneurs (small grocery stores), a sandwich shop and an Indian restaurant. She also says the Hard Rock Cafe is closing down. "We can't say it's directly related to the Grand Prix, but it's obvious."

The mood changed in the summer when Ecclestone declared he wanted the race back. In early August, the "F1 Supremo" told Switzerland's Motor Aktuell magazine "I promise we will be in Montreal in 2010. Everyone in Formula One loves the Canadian Grand Prix."

Reaction, though, was cautious. They had heard this before; at one point, rumours swirled that Montreal would take the race back from Abu Dhabi in 2009 because Yas Island wasn't ready. "Between Ecclestone's assuring words and the reality of F1 returning to Canada is a gulf the size of Mexico," Dean McNulty wrote in the Toronto Sun, referring to the difference in money. "There's not a bridge in the world that can span that gap."

But, during a subsequent interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Ecclestone said: "We have an 'in-principle' agreement of how we're going to make the race happen. It states that we are going to have a next seven years ? in Montreal, of course."

Finally, last month, a preliminary agreement was reached and when the F1 calendar was released last month, Montreal was back - albeit provisionally - with the race scheduled for June 13. Whether the race actually takes place still depends on a final contract being agreed between the league and the city of Montreal.

As if to reinforce the fickleness of F1, Abu Dhabi also discovered that it had lost the privilege of hosting the final race of the season next year. That honour now goes to Brazil.

In September, Legault also issued a release saying he and the Formula One Administration had settled their contractual dispute, though it is unclear what impact this has on the ongoing talks. In the release, Legault confirmed he was still stepping aside as promoter. During our interview Legault says he's content to stay in the stands. "It would have been a difficult year for us to put on a race," he reflects. For the first time in years, he went to his summer house during the first weekend in June. "There was no nostalgia. Even if we had the race, the economic impact meant it would not have been what it was before. When it was all said and done, maybe it was best that we did not have a race this year."

But Greene puts a slightly different spin on it, "The loss of it might have been good, in fact, to remind people of the greatness of Grand Prix."

If - as is looking likely - the deal goes through, the new organiser is likely to be Francois Dumontier, who ran the Nationwide Napa Auto Parts Nascar race at the end of August. Flageole, however, sees the damage done. He had not missed a Grand Prix since 1978, and worked at the race throughout the years as a pit exit man, assistant to the starter and other roles. When we met, Flageole, like all Quebec racing fans, was gearing up to cover the Nationwide Nascar at the end of August, which featured Canadian drivers Patrick Carpentier and Jacques Villeneuve. Organised by Dumontier, it was set to be the racing highlight of the year.

"F1 is not the 'in thing' any more," Flageole says. "If you are a local fan - and I'm not talking Mr Millionaire - you will have a budget for a race. There is only so much you can spend for one event. Stock car is the new phenomenom in Canada."

Ticket prices have risen as F1 seems to be targeting a high-end audience, a perception reinforced by the introduction of the Bahrain and Abu Dhabi races.

"Today, F1 is a luxury brand on the same scale as, let's say, Louis Vuitton," Legault says. "It's image is intertwined with yachts and Monaco."

This is one reason, he says, the carmaker Honda pulled out of F1.

Nascar, on the other hand, is the populist sport. The stock car series has taken over in North America and is known for the crashes, blatant product placement and well-fed fans.

Two lower levels of Nascar racing - the Nationwide Series and Canadian Tire series - have so far made it to Canada, and have been well received. Unlike an F1 event, where a fan's best chance of seeing a driver is at a staged press conference, Nascar racers mingle with the crowd. There is a set autograph session in the pit, where anyone can get a photo with a driver.

Quebec drivers are also finding success in Nascar. At a recent Canadian Tire race in Trois Rivières, three French Canadians were in spots one, three and five in the race. Andrew Ranger, a 22-year-old driver from Roxton Pond, Quebec, won the race.

"Someone in the US will grab him and he'll become the next Gilles Villeneuve, in Nascar," Flageole says.

If he does, there is nothing stopping stock cars from recreating 1978's magic moment - but at the time of our meeting Flageole was content to return to the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve in the summer, whatever race was on.

"There's going to be tons of kids in two weeks' time in Montreal," Flageole said. "They can relate more to a Nascar car than an F1 car ? F1 is now out of reach for normal people. I don't think anything Bernie or FIA decide to do will bring back the race to what it was 40 years ago."

Montreal, restart your engines

FeatureThe Canadian city was devastated when it was dropped from the Formula One calendar this season. But now that the race has been provisionally put back on the circuit, John Mather looks at what this means for the city and asks what lessons Abu Dhabi can learn.

Most popular today